A humanist perspective on the crucifixion story.

Historical, revelatory or legendary, the crucifixion of Christ represents the story of many. Whatever your personal faith or none, the modern scholarly view on whether the man named Jesus existed ranges from ‘probably’ to ‘possibly’, and the story of Christ in the gospel narrative reflects a wider human story: that of thousands upon thousands of nameless and forgotten individuals who were crucified at the hands of the Roman state.

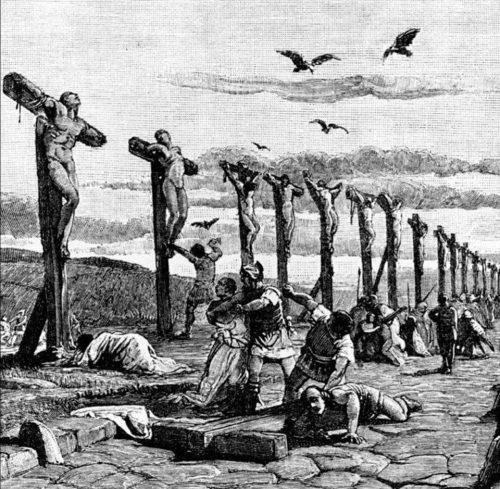

Anyone who assumes that crucifixion was an unusual or extraordinary event in Roman times should consider the case of the rebels led by Spartacus. This low-born Thracian gladiator-slave led a revolt so successful that it caused considerable embarrassment to the ruling Senate. When Crassus finally crushed the rebellion in 71 BCE, he ordered the crucifixion of an estimated 6,000 slave-rebels along the Appian Way, the main road leading out from the city of Rome; he also brought back the ruthless practice of decimation to punish and terrorise the cohort of soldiers that he deemed to have failed him the most in his earlier attempts to quash the rebellion.

Crucifixion was public and humiliating – deliberately so – and its use in the case of the slave-rebels illustrates several important points about this notorious and brutal method of execution. Its aim was to demean the victim and intimidate the observer – this was what happened to you when you challenged the Roman rule of law. Crucifixion was a servile supplicium – reserved for slaves and foreigners, non-Roman citizens, deserting soldiers, pirates and insurgents. Wealthy Roman men were often removed from society due to political machinations or the whim of current authority, but never was crucifixion used as the method to dispense with them.

In its broadest definition, crucifixion meant that the victim was impaled and/or tied to some form of frame, cross, stake or tree and left to hang for anything from several hours to several days. Causes of death included exhaustion and shock brought on by extreme pain and exsanguination (sometimes in part from a scourging prior to the crucifixion), heart failure and/or pulmonary collapse from the immense pressure put upon the victim’s heart and lungs; the victim’s demise could be hastened dramatically by increasing the intensity of this pressure, hence the common practice of breaking the legs to precipitate collapse. It was a sadistic and grotesque formula for murder, exploited in extremis by the Romans.

It is not clear whether the emperor Constantine outlawed crucifixion in the 4th Century CE, as is claimed by Christian triumphalist writers, but certainly it had been outlawed in the Roman empire by the mid 5th century. However, the Classical world is not the only context in which this abhorrent method of slaughter has been practised. Japanese haritsuke started with the execution of 26 Christians in Nagasaki in 1597 and recurred intermittently up until the last century. Islam has also subsumed the practice, with verse 5:33 of the Qur’an calling for the crucifixion of those who wage war against Allah or the Prophet Muhammad. Crucifixion is still practised in some Islamic countries and there have been recently-documented cases in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran, Syria and Yemen; it is most commonly used to make a degrading and threatening showpiece of the victim’s body rather than as a method of execution, but this is not exclusively the case.

The Easter story means nothing to a humanist from a spiritual perspective; we do not believe that Christ was the son of God, nor do we believe that he died for our sins and was resurrected. Yet each year the human side of the Easter story can serve as a sober reminder of man’s inhumanity to man. In a modern context, we can and should take action by giving support to the work of organisations such as Amnesty International, who campaign tirelessly and effectively against the use of torture and capital punishment right across the globe.

But as a Classicist, I cannot help but see the story of Christ within its ancient milieu and recall the incalculable number of wasted human lives that resonate through its narrative. In the name of ‘Roman civilisation’, hundreds of thousands of ordinary people were tortured and crucified, forgotten souls with no afforded legacy of reverence or pious gratitude to preserve them in the conscious minds of the living.

At this time of year, I choose to remember them.

This piece was first published in Humanist Life in 2016.