Given the undeniable unfairness baked into Roman society, it might be a surprise to some that the Romans embraced a democracy of sorts. Only a small fraction of people living under Roman control could actually vote, but male citizens during the period when Rome was a Republic did have the opportunity to cast their vote for various administrative positions in government. The Latin verb “to choose”, which forms the title of this blog post, is what produced the participle electus and gives us the modern word election.

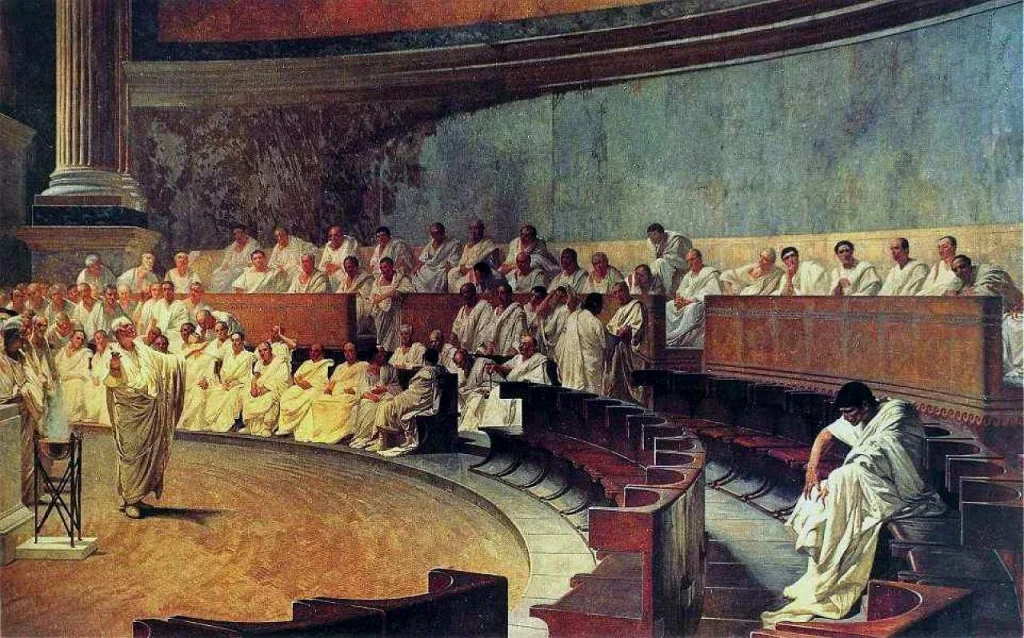

In the 6th century BCE, with the overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the city-state of Rome was re-founded as a Republic and by the 3rd Century BCE it had risen to become the dominant civilisation in the Mediterranean world. The ruling body known as the Senate was made up of the wealthiest and most powerful patricians, men of aristocratic descent. These men oversaw both the military campaigns that brought expansion and wealth to Rome and the political structures that managed its society. At the beginning of the Republic, only the Consuls were elected, but in later years Roman free-born male citizens could vote for officials in around 40 public offices which formed a complex hierarchical structure of power. Yet this public performance of voting did not really offer the citizens any kind of real choice. If you’re feeling depressed about the choices offered to you in your polling booth today, take heart: things were considerably worse two thousand years ago (even if you were a man).

Candidates for office under the Roman Republic were originally selected by the Senate and were voted for by various different Assemblies of male citizens. These Assemblies were stratified by social class and the weighting was heavily skewed in favour of the aristocracy. In the early years of the Republic, candidates were banned from speaking or even appearing in public. The Senate argued that candidates should be voted for on the merit of their policies, rather than through rhetoric and personality; in truth it meant the general public had no real opportunity to hear candidates’ arguments or indeed to hold them to account. In the later Republic the ban on public oracy was lifted and the empty promises so familiar to us today abounded, alongside some good old-fashioned bribery which – while theoretically illegal – was widespread. As the practice of electoral campaigning developed things did begin to change, with the pool of candidates no longer tightly limited to a select group of aristocrats under Senatorial control. In the long-term, however, this led to even greater misery for the citizens. They lost what little democracy they had during the Roman revolution, when what should have been a righteous and deserved uprising against the ruling oligarchy ended up turning into something arguably worse. Rome’s first ruling emperor, Augustus Caesar, claimed that voting was corrupt and had been rigged by the Senate for years in order to perpetuate the power of a handful of aristocratic families. His neat solution was to abolish voting altogether. Be careful what you wish for?

Once the early ban on public oracy was lifted, a key component of public campaigning during the Republic was canvassing for votes in the Forum. A candidate would walk to this location surrounded by an entourage of supporters, many of whom were paid, in order to meet another pre-prepared gathering of allies in the central marketplace. Being seen surrounded by a gaggle of admirers was hugely important for a candidate’s public image and was worth paying for. Once in the Forum, the candidate would shake hands with eligible voters aided by his nomenclator, a slave whose job it was to memorise the names of all the voters, so that his candidate could greet them all in person. The man running for office stood out in the crowd by wearing a toga that was chalk-whitened called the toga candida: it is from this that we get the modern word candidate.

To further attract voters among the ordinary people, candidates gave away free tickets to the gladiatorial games. To pay for such a display a candidate either had to be extremely wealthy, or to secure the sponsorship of wealthy friends. Cases are documented of men ending up in ruinous debt as a result of their electoral campaigning. Several laws were passed attempting to limit candidates’ spending on banquets and games, which evidences the fact that that the Senate didn’t like electoral corruption except when they were in charge of it.

Democracy under the Roman Republic was very much controlled by the select few male members of the aristocracy who held seats in the Senate. They essentially held all of the power, having been born into wealthy patriarchal families. The majority of people who inhabited the Roman world were not allowed to vote, including women and slaves. It is striking and not to say infuriating how many modern sources on Roman voting talk about “citizens” and “people” without seeming to feel any need to clarify that they are talking about male citizens and male people only. We do have evidence that women in the wealthiest families put their money and their energy behind their preferred male candidates, most usually because they were members of the same family. Electioneering in the form of visible graffiti in Pompeii evidences women’s support of their husbands, fathers and brothers but this is all produced by women of considerable means; what the poorest women in society thought and felt about the men who controlled their lives is anybody’s guess.

Palazzo Madama, Rome