If you want to witness polarised debate in the education world, then the platform formerly known as Twitter is where to find it. Teachers rarely argue in person, but will quite happily rage at each other in Elon Musk’s rapidly-disintegrating playground. There have been attempts to shift us all onto Threads, but so far the battleground remains in one place. X is where we shout at each other.

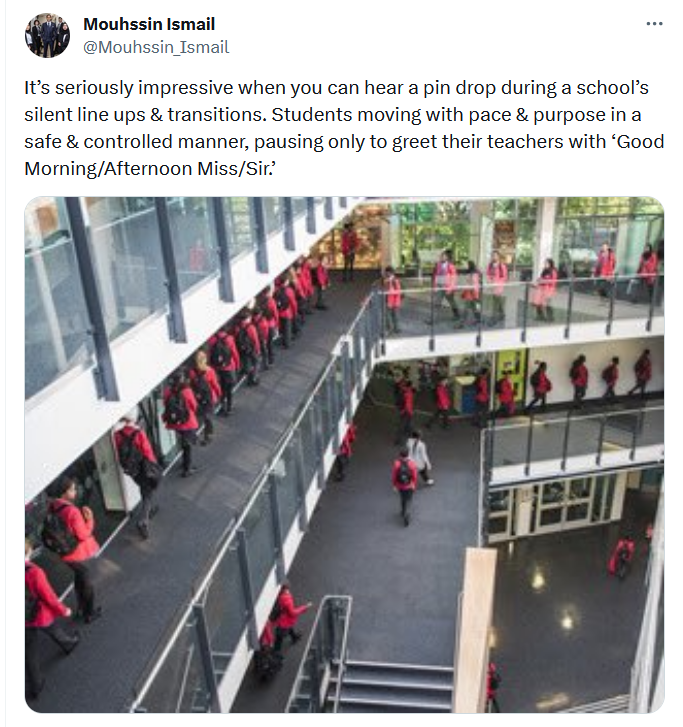

This week’s argument has raged around the concept of “silent corridors” – specifically, whether it is necessary, appropriate or desirable to ask students to move between lessons without talking. Schools which elect to do so usually have rules about the way in which students walk and space themselves too: for example, single file, a certain distance apart. Five days ago, Executive and Founding Principal Mouhssin Ismail shared this tweet about an unnamed school:

The moment I saw it, my heart sank. Not because I disagreed with it, but because I knew the response it would get from certain quarters. Despite this, nothing could have prepared me for the level of vitriol this tweet provoked, from the downright nasty to the genuinely unhinged.

“Unnatural, unnecessary and unkind” said Richard Clift, in a masterful tricolon. “I am hoping this is a spoof” said John Cosgrove. “Looks like some kind of dystopian nightmare scenario with cyborgs mechanically marching to hasten humanity’s doom. Hideous apparent absence of personality, life, joy ..” So many assumptions about the entire institution, its educational philosophy and the manner in which it asks its staff to teach, all on the basis of how students are told to move around the school between lessons. “This is seriously disturbing and unnatural”said Lin Holden. “It looks like a scene from Gilead. Under His Eye.” Others have no need of allusions to science fiction or dystopian literature to express their distaste – they find the school’s corridors reminiscent of real and existing totalitarian regimes: it’s “like something from North Korea” said Marc Davenant, who has evidently never been to North Korea.

More personal attacks lined up in the responses too. “This should fill you with shame. Why are you boasting about it?” said Helen Salmon. “Hey Google, show me a school that looks like a prison” said David Smith. More succinctly from Joao Arajuo, “this is SICK”. The comments went on and on, overwhelmingly filled with outrage and all assuming that anyone who asks children to be silent and ordered must hold them in contempt. Perhaps most interesting were the ones which did as we all do, which is draw on our own experiences: “unnecessary and frankly weird,” said Paul Lucas. “I went to a highly disciplined all boys grammar school and it didn’t feel like the army. Ever. Mostly turned out happy young men comfortable in their own skin, including a lot of real eccentrics.” Lucky Paul to have hailed from such privilege.

I too went to a school that many will see as privileged. It was only when the debate started raging about silent corridors that I remembered the fact that the school I attended had them. I had honestly forgotten. I spent seven years in my small, private secondary school for girls and remember all sorts of weird details about it (quite honestly, there are some seriously weird details to remember), but silent corridors was not something that had lodged in my mind. Only when I started to read how grossly oppressive they apparently are did I recall that this was the school rule. In actual fact, lessons were often quite noisy and discipline was not always effective (most of the staff had no training), but silent corridors was a given. Did I find it so terrifying that I have repressed the memory? I don’t think so. I think I didn’t remember it because it didn’t matter.

I would be the last person to defend the school I attended, which at the time (we’re talking the 1980s here) was horrendously old-fashioned and was indeed genuinely oppressive in some ways. The school was deeply religious and was unwilling to tolerate dissent from religious teachings, which was tough for a heathen like myself. There were a great deal of seriously stupid, unjustifiable and pointless rules, some of which detracted from effective learning. Not all staff were kind. Yet out of all of the things I would change about that place, silent corridors would not be one of them. Lesson changeover was, in fact, a blessed relief and an opportunity for down time; a little time in your own head before the next onslaught.

One of beliefs held by people who dislike the concept of silent corridors is that they are not only oppressive but they are unncessary. “The idea that children chatting to each other has to be bedlam or dangerous is ridculous” said Graham Chatterley, whom I engaged in a discussion for a while. He believed that silent corridors are an issue for neurodivergent students who, in his words “have been masking and holding everything in for an hour’s lesson” and “need to have the opportunity to relax for two minutes”. I do not disagree. My own experience, however, is that silent corridors enable this and my own experience of teaching neurodivergent children is that they are most exhausted by the noise and general sensory overwhelm of modern schools. Many of them go home and lie in a darkened room for two hours when they get home, so over-stimulated are they by the lights, the noise and the hubub. Graham told me that I had “an extremely narrow definition of neurodivergent” and maybe he’s right – there may be neurodivergent students that don’t find consistency, quiet and clarity more helpful than noise and excitement, but in 21 years of teaching I have not met one.

Here’s the thing. None of the schools I have worked in had silent corridors. They were rated at least “Good” for behaviour, were oversubscribed and were generally considered to be places where people wanted to send their children. Leadership did not believe in super-strict regimes so silence was not expected, nor was walking in single file. Corridors were, however, supposed to be calm and students were advised to move quietly, swiftly and purposefully between lessons. All sounds well and good, doesn’t it? The problem is, because students were not taught how to do things such as lining up and moving in single file, and because this was not consistently reinforced by all staff, lining up rarely was lining up and moving about the school was something of a rabble without a cause. Students also struggled with order when it mattered, for example during a fire drill.

Worse than this, when it comes to every day life working in a school, there were many times when I found the corridors an issue. The problem with loose, liberal guidelines like “move between lessons swiftly and quietly” is they are too vague. One person’s “quiet” is another’s “a little too noisy”. And what does “swift” mean? Racing along? Not dawdling? Both staff and students were unclear what the expectations were and staff (due to their lack of clarity and lack of confidence) were haphazard in enforcing them – you can’t enforce what you’re vague about. All of this leads to wasted time between lessons and sparks arguments between students and staff. Worse than this, however, in a large school where silence is not expected between lessons, the noise level from normal chatting and laughing and the movement created by large numbers of teenagers roaming about is so great that this often leads to exponential increases which can very quickly tip over into chaos. One student starts pushing, one student squeals and the next thing you know the corridor is a heaving, screaming mass of bodies pushing and shouting. I do not exaggerate. This happens regularly in small pockets in all schools at certain pinch points. Staff used to have various ways of managing this. One carried a whistle and used it rather effectively. Tall men with booming voices were useful. We used evasive action, by releasing classes in a staggered order, holding one class back while another was moving past. Finally, it was standard practice in the school that any child (or indeed staff member) with any kind of injury was allowed to leave lessons early “to avoid the hustle and bustle of the corridors”. The message seemed to be that potential chaos in the corridor was unavoidable, therefore evasive action should be taken if an individual was at heightened risk – never mind that the situation itself is risky for all.

My personal view is that order and silence in corridors is highly desirable. I believe that they keep students and staff safer than in the corridors I have experienced during my career. I believe that they prevent less time being wasted. I believe that they help students to prepare for later life, in which there are times when one must switch between silence and vocalisation at the drop of a hat. I do not believe that they are in any way oppressive and am genuinely at a loss to understand those who do. In some school environments, silent corridors are frankly essential and staff are failing in their duty of care if they do not provide them; this is something which Clare Sealy wrote about some time ago and for those of us who have only lived and worked in relatively privileged environments, this blog is essential reading. Please, if you think that the staff who work in these kinds of schools don’t care about the children they are working with, you definitely need to read it.

My hypothesis, for what it’s worth, is that my generation and those coming after us have consistently confused authority with authoritarianism. The worst thing that one can be accused of is being illiberal, and the best way to avoid this is to eschew all forms of authority. Ironically, in some quarters, this mindset is so entrenched it has become undeniably authoritarian – you must believe what I believe, and if you don’t you must be an oppressor. It would do us all good to remind ourselves that we are all on the same side: we all want children to be safe, supported and happy in school and for them to receive the best possible free education. What we differ on is how to achieve this.