You could be forgiven for thinking that Gregg Wallace’s video was the most explosive thing to happen on social media this week, but you would be wrong.

Picture the scene: a young, female academic at Cambridge shares a happy picture of herself, smiling and clutching her freshly-acknowledged PhD thesis in English literature. Ally Louks, now Dr Ally Louks, probably thought that her message of celebration that she was “PhDone” would be liked by a few and ignored by the majority. Yet her post at the time of writing has been seen by hundreds of thousands of people and Ally has received torrents of abuse, some of which beggars belief. The whole storm has sparked outraged discussion on all sides – most of it thoroughly ignorant – about what a PhD is or should be.

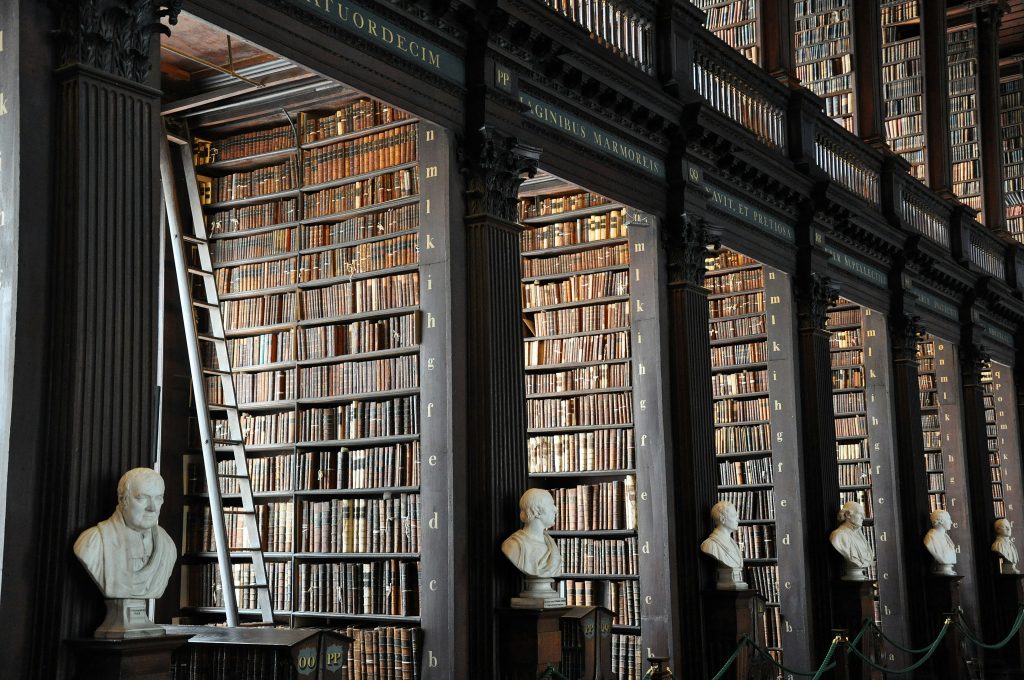

Here’s the thing, for those of you that haven’t been there. A PhD is like going potholing: you wriggle down into some difficult spaces and explore the subterrain. Nobody will ever know those particular underground passages better than you, because nobody else is ever likely to go there or, indeed, even want to go there. The reason you’re awarded the PhD is because you have traversed new terrain and – in the judgement of the potholing community – you are the first to do so, or you have uncovered a sufficient number of nooks and crannies that previous potholers did not comment upon. Most of the time, you don’t find an underground palace, a glistening river of stalactites or a dazzling crystal chamber: you simply wriggle your way back up to the surface and get on with your life. Your thesis will sit on the shelf of whichever institution recognised it and – if you’re lucky – it will be consulted by a tiny handful of niche-hole specialists over the next few decades, the number of which you could count on one hand.

Personally, I blame Stephen Hawking. During his doctorate, he hit upon a leap of understanding so brilliant that it changed the direction of theoretical physics forever. Most of us don’t manage that. This does not mean that our PhDs are not worthy of the title: it simply means that most of us are – demonstrably – not a genius like Hawking. There is a reason why Hawking has been laid to rest between Newton and Dawin: he is right up there with those two when it comes to the significance of his contribution to his field. Yet many people seem to assume that Hawking is an example of what is expected of a PhD candidate – a particularly famous example, perhaps, but an example nonetheless. In reality, most research is utterly banal and unimportant: it’s not going to shake up our understanding of the fabric of the universe.

Louks’ PhD sounds – to me – rather fun. Okay, I’m one of those wish-washy artsy types that got a PhD in Classics, not theoretical physics, but I reckon her thesis “Olfactory ethics: the politics of smell in modern and contemporary prose” sounds like a more stimulating read than a huge number of PhDs that have passed under my nose over the years (pun intended). In response to the unexpected interest in her work, Louks shared her abstract, which only further made my nostrils twitch. Her thesis explores “how literature registers the importance of olfactory discourse – the language of smell and the olfactory imagination it creates – in structuring our social world.” Her work looks at various authors and explores how smell is used in description to delineate class, social status and other social strata. I mean … fine? No? Quite why a certain type of Science Lad on the internet decided that this was a completely unacceptable thesis baffles me. Apparently, there is a certain type of aggressively practical chap, who believes that exploring how things are represented in literature and how that literature has in turn helped to shape our world is utterly unworthy. Well, more fool them. They should read some literature. I suggest they start with Perfume by Patrick Suskind, a modern classic that is quite literally a novel about smell.

I’ll confess that the whole thing has left me feeling quite jumpy about my own thesis, which in 1999 was welcomed as an acceptable contribution to my very narrow, very obscure corner of the underground caves. Once I had seen the reaction to Louks’ abstract I decided to re-read my own. Having done so, I concluded not only that it would sound utterly barking to the rest of the world, it sounded utterly barking to me! This was a field in which I was immersed at the time but have read nothing about since I walked out of the room in which my viva took place.

The viva itself is something that most people do not really understand and is difficult to explain. It is not an examination. Short for viva voce, which is Latin for “with the living voice”, the viva is there in principle for the PhD candidate to demonstrate that they are the author of their own work. In practice, it is also an opportunity for the examiners to quiz the candidate and explore their hypothesis further. The examiners may have questions and it is common for them to advise corrections and amendments; often, the examiners make the passing of the thesis conditional on these amendments. Best case scenario (and one enjoyed by Ally Louks), the examiners pass your thesis with nothing more than a few pencil annotations, none of which require attention for the thesis to be accepted. Worst case scenario, they say that your thesis is a load of old hooey and that you should not – under any circumstances – re-submit it, corrected or otherwise.

While the worst-case scenario is rare and indicates a profound failure on the part of the candidate’s supervisor, who never should have allowed the submission, it does happen on rare occasions. The last time I saw one of my old lecturers from my university days, he reported being fresh from a viva on which he had acted as an external examiner and had failed the thesis. This happens so rarely that I was agog. Having been so long out of the world of academia, it is impossible for me to express in simple terms the intellectual complexities that he explained were the reasons behind his decision, so I shall have to quote him directly: apologies if the language is too academic for you to follow. “Basically, it was b*****ks,” he said. “I mean, don’t get me wrong, it was kind of brilliant b*****ks: but it was b*****ks nevertheless.” That poor candidate. I ached for him. I also found myself recalling the gut-wrenching moment during which Naomi Wolf’s PhD thesis was exposed as fundamentally flawed by Matthew Sweet, live on Radio 3. If you’ve never listened to the relevant part of the interview, I highly recommend it: it is – especially for those of us who have submitted a thesis for judgement in the past – the most toe-curling listen imaginable. Wolf’s entire thesis appears to have been based on a misunderstanding of a legal term, which Sweet discovered simply by looking it up on The Old Bailey’s website. Wolf’s thesis had been passed at Trinity College, Cambridge, an institution that would be hard to beat in terms of intellectual clout and reputation, so quite how this happened is mind-boggling and shameful.

The reaction to Souks’ thesis does, I suspect, have a great deal to do with the increasing suspicion with which academia is viewed, and in many ways I am not unsympathetic to people’s disquiet. There is, without question, a good deal of nonsense (or b*****ks, to use the technical term) talked in a lot of fields, particularly in the arts and social sciences. Yet the vitriol with which Souks was criticised has nothing to do with this. Her abstract, to anyone with even a grudging respect for the field of English literature, makes intellectual sense. No, the roasting of Souks and her work betrays a profound and depressing ignorance as well as a nasty dose of good old-fashioned cruelty. Before people decide that an entire field of study is unworthy of merit, they should maybe ask themselves whether there is even the tiniest possibility that they perhaps don’t know enough about it before they pounce. One can but hope that these people who value their rationality so much will next time run a more scientific test, rather than dunking the witch to see whether she floats.