“Life is like a game of cards. The hand you are dealt is determinism; the way you play it is free will.”

Jawaharlal Nehru

Currently, I am obsessively plugged in to an audiobook, the latest release from my favourite author, Liane Moriarty. Moriarty writes what is often scathingly referred to as “chick lit”: a genre which at its worst can be undeniably vacuous, but no more so than the two-dimensional thrillers churned out by authors marketed to men. The withering contempt with which “chick lit” is viewed says a lot more about how society treats the everyday lives and concerns of women than it does about this particular genre of popular fiction.

It is undeniable although perhaps a little depressing that Moriarty is an author unlikely to be read by vast quantities of male readers. Her stories revolve around people – mainly suburban women – and the thoughts inside their heads. Often there is an unfolding plot, but the focus is on the development of character and relationships rather than on action or suspense. Moriarty is an absolute master of the genre and writes with an effortless charm that belies her talent; the best authors make it look easy when it isn’t. It’s a great shame that more men aren’t interested in some of the things which interest women, and a truth that I have pondered the reasons for on and off. I speak as someone who has read quite broadly and have flirted with books categorised in modern times as “lad lit”: I am a huge fan of Martin Amis and if you haven’t read David Baddiel’s forays into novel writing in this genre then you should – they are annoyingly good. So if I, as a woman, can enjoy books written from a male perspective and read by men, I find it somewhat irksome that so few men have the desire to show any kind of interest in the fiction favoured by women. Anyway, I digress.

Much as many of Moriarty’s books (perhaps most famously Big Little Lies) focus on the lives of suburban women, some of them are intricately plotted and follow the lives of a complex set of characters, all of which cross paths in various ways and with a myriad of consequences. Because of this, I was greatly surprised when I heard the author interviewed and she revealed that she writes without a plan. Prior to her most recent release, the last novel she wrote called Apples Never Fall followed the tensions and anguish within a family from whom the matriarch has disappeared: most of the novel we spend wondering what has happened to this character (including whether she has merely walked out of her life or has been horribly murdered by someone within it), and Moriarty reports that she too spent much of her writing time wondering the same thing. She had not, by her own account, decided what had actually happened to this key character when she began to write the book. She started with the idea of the disappearance and discovered the truth behind it along with her characters. It is perhaps this very unconventional approach to plotting that enables her to write with such authenticity – she’s not dropping hints or trying to plant red herrings in relation to the real outcome, for she has no idea what that outcome will eventually be.

I am around one third of the way through Moriarty’s latest and am gripped as ever by her writing. Here One Moment is perhaps her most ambitious novel yet as it circles around the idea of free will and destiny. In summary, the scenario is that a group of people on a flight from Hobart to Sydney are each pointed at by a woman on board the flight and told the supposed time and manner of their death. Some passengers are given what amounts to welcome news by most people’s standards (heart failure, age 95), others – inevitably – are told that they will die very young. Some are even told that their death will be as a result of violence or self-harm. The rest of the novel is about the fall-out from this thoroughly alarming and unscheduled in-flight entertainment.

One of the ideas explored in the novel is the impact that such an experience might potentially have, not only on the feelings of those receiving the predictions but on their actions too. One of the passengers pays a visit to another “psychic” after the flight, and this “psychic” points out to him that he will not be the same person after the reading as he was before it. He points out that whatever he says to his client will make him act differently and that this will then potentially have an impact on the outcome of his life. Moriarty refers constantly to the idea of chaos theory throughout her writing – the idea that one small event in nature has a ripple effect that causes huge impact in other areas. At the point in the novel where I am right now, a mother who has been told that her baby son will die by drowning while still a child has elected to take him to swimming lessons. He takes to the lessons like the proverbial duck to water and it becomes clear that he is going to become a huge lover of swimming. As readers, we now sit with our hearts in our mouths and await the inevitable: will the mother’s decision to take her child to swimming lessons, sparked solely by the psychic’s so-called prediction, end up leading to the death of her child in the future?

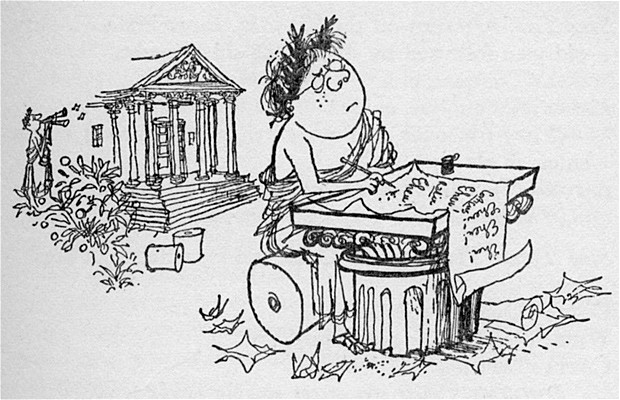

The same thought experiment was run by a Greek playwright called Sophocles almost 3000 years ago. He wrote what I would argue is perhaps the most influential work of literature ever published, in the form of the tragedy called Oedipus Rex. Most people know the name “Oedipus” only as a result of Freud’s early 20th century ramblings about motherhood and sexual repression; very few people have any idea what a frankly brilliant and chilling story that of Oedipus was when it was written. It is emphatically not a story about motherhood, nor is it a story about sexual repression; to be honest I don’t think I can ever forgive Freud for making it so. Oedipus Rex is a story about destiny, about free will and about the extent to which we have control over either of those things. If you don’t know the story, it can be summarised as follows …

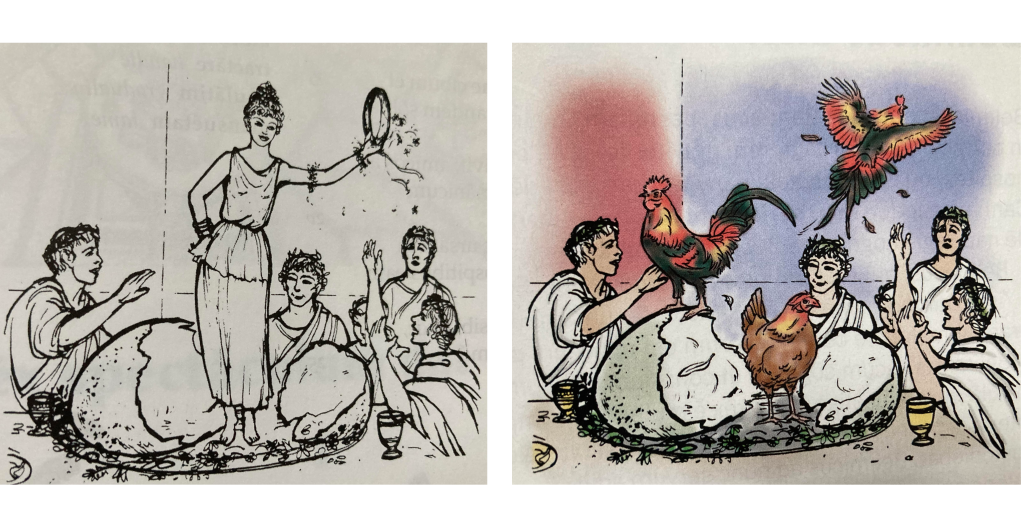

In ancient Greece, a king and queen are horrified to be told by an oracle that their baby son will grow up to murder his father and marry his mother. Terrified by this ghastly prediction, they send the baby away to be exposed on the hillside and die. The kindly old shepherd gifted with the unhappy task cannot quite bring himself to do the dreadful deed, so he ends up passing the baby to another ruler and his wife in a far-distant land who are childless, and they bring the baby up as their own. The baby is named Oedipus. He has no idea that he is adopted.

When Oedipus grows up, like all curious young men, he too consults the oracle and asks his destiny. The oracle tells him that he is destined to kill his father and marry his mother. Horrified, he does the only sensible thing: he removes himself from his family home and goes off on his travels, thus removing any possible risk of somehow murdering his father and marrying his mother. Oedipus believes that he has taken control: he is the master of his own destiny and he has cheated the oracle. Trouble is, remember … he doesn’t know he is adopted.

Several months into his lonely travels, Oedipus gets into an altercation on the road with an arrogant older man who tries to tell him what’s what. Long story short, Oedipus does the only thing any decent red-blooded young male would do, he kills the old fool. Afterwards, he continues on his travels and eventually comes to a kingdom which is in a bit of trouble because it’s being harassed by a nasty monster. Clever Oedipus defeats the monster by solving its riddle and – would you know it – it turns out that the king of this particular dominion has recently died and they’re in need of a chap to take over. What a stroke of luck! Oedipus marries the widowed queen – who is granted a little older than him but still young enough to bear children – and becomes King of Thebes. The rest, as they say, is a truly horrible history.

The whole point of Oedipus’ story is exactly the thought experiment that Moriarty is playing out in her novel. To what extent does a sense of destiny itself predetermine our actions? To what extent do people inevitably fulfil the path that they are told lies in front of them? It is easy to point out that if the oracle had not said what it said – on either occasion – the story of Oedipus would not have unfolded as it did. In the ancient world, the story was taken as a morality tale about man’s arrogance: humans are convinced that they can outwit the gods and cheat their destiny, and that arrogance begins and ends with asking the question. If nobody had asked, would nothing have happened? Does the asking trigger the event?

It is easy to assume that these big philosophical questions don’t affect our lives on a day-to-day basis, but in fact this loop of thought is inescapable and resonates in daily life. During my career, a trend came and (thankfully) went of sharing what were laughably called “predicted grades” with students. These grades were not teacher predictions (although teachers are indeed asked to make such psychic predictions and that nightmare continues) but based on a crushing weight of data that looks at “people like Student A” and attempts to make a mathematical prediction about how “a person like Student A” is most likely to perform in an exam. All sorts of data get included in the mix, from prior academic performance to socio-economic background. The happy news that a bunch of data analysis that hardly anybody fully understands “predicts” that Student A is likely to get a Grade 3 or below was – until alarmingly recently – shared with Student A. What an absolute travesty. I will never forgive the system for sitting a child down and telling them that the computer says they’re likely to fail. Likewise, I have seen children who are “predicted” a line of top grades spiral out of control under the pressure. For heaven’s sake stop telling kids what “the data” (our new name for the divine oracle) says about their destiny. It’s a seriously grotesque thing to do.

For similar reasons, I know parents who are understandably jumpy about their children being labelled as anything. Who doesn’t remember well into middle age having “he’s shy” or “she’s anxious” being said over their head, while they were going through an entirely normal phase of being wary of strangers? Before you know it, the label of “shy” or “anxious” or whatever the grown-ups have decided befits you becomes you. I am absolutely in support of my friends who will not have their children referred to in this way: if history teaches us anything, it’s that people tend to fulfil their destiny. So be careful what path you pave.