OCR GCSE Latin Set Text 2023-2024

One day, or so my fantasy goes, OCR will publish the lines of the Virgil set text and every single line of the prescription I will have taught before. The fact that this has not happened in the 21 years I have been teaching is a testament to their ingenuity, their record-keeping and perhaps their sheer determination to make the lives of all Classics teachers as fiendishly challenging as possible.

Happily, the text this time around has a significant number of lines in common with previous specifications. My record-keeping is not as meticulous as OCR’s appears to be, but from the dates on the files I have just been hunting through, it looks like the 6th book of Virgil made an appearance in around 2010 and prior to that in around 2003. This year’s specification includes:

Lines 295–316: I have taught these lines before.

Lines 384–416: I have taught these lines before.

Lines 679–712, 752–759, 788–800 I cannot find in my resources.

Teaching an epic: where to begin?!

One of the biggest challenges that confronts us when embarking on the Virgil text is how much to teach students about the work as a whole and its place in the historic canon. To start with, it is most important that students are given a very basic introduction to the definition of an epic. I usually go with this one:

A long poem, typically one derived from ancient oral tradition, narrating the deeds and adventures of heroic or legendary figures or the past history of a nation.

After that they need to understand who Homer was on a very basic level: i.e. that he wrote in Greek, and that he was the first and the greatest of the epic poets and thus the father of Western literature. They also need to understand that epic stems from an oral rather than a written tradition.

Many students will have heard of some key Homeric stories, so I tend to hang the difference between the Iliad and the Odyssey around those – Trojan War/Achilles/Hector versus monsters like the Cyclops or Scylla and Charybdis. I also explore how the word “odyssey” has entered into the English language.

Following their bluffer’s guide to Homer, students need to understand that Virgil’s poem was commissioned as a work of national pride by Augustus – they don’t need to understand the ins and outs of Augustan propaganda, but they usually find it interesting and indeed relevant to understand that this is what was going on; how much detail you explore with them will of course depend on the amount of teaching time that you have, but it is certainly important for them to understand that the Aeneid was deliberately created for a purpose, whereas Homer’s writings are the result of a process of evolution.

As the prescription is taken from Book VI, it is also important I think for students to understand that the Aeneid is split into two halves, with Book VI forming the bridge from one to the other. The first half is a loose imitation of Homer’s Odyssey (journeys and monsters) and the second is the same for the Iliad (fighting and self-definition). Book VI obviously echoes the descent of Odysseus into the Underworld in the Odyssey, but it also marks the crossover point between the two halves of the work and therefore the shift in tone and mindset towards the Iliadic half of the poem.

The journey to the Underworld is the final stage of Aeneas’ odyssey to Latium, which is mapped out in the first half of the poem. Aeneas’ experiences in Tartarus and Elysium offer him a kind of closure to his Trojan past and prepare both him and Virgil’s audience for his future destiny as the founder of the Roman people. As he emerges from the Underworld, reeling from the images of Rome’s future glories, Aeneas manifestly becomes the proto-Roman victorious general that he must be for us in the Iliadic half of the poem. Through that famous pageant of future Roman luminaries, Book VI also forms Virgil’s central piece of propaganda within the poem; while there are key pieces of conspicuous self-definition at each end of the epic (in the speeches of Jupiter to Venus in Book I and to Juno in Book XII), Book VI is without doubt the most chest-thumping of moments for any self-respecting Roman. This is partly why it is so crucial for this proscription that students understand the Aeneid as a commissioned work of propaganda; Aeneas’ time in the Underworld also affords Virgil the opportunity to map out the moral standards of Augustan Rome, echoed in the cycle of reward and punishment that he witnesses.

At the start of Book VI, which you will want to read in translation with your students, Aeneas’ visit to the Sibyl builds an atmosphere of awe and mystery, with Aeneas’ ritual prayers and the Sibyl’s prophecy. The sense that Aeneas is on a destined path to glory is underlined by his assisted discovery of the golden bough and the Sibyl’s prophecy that “another Achilles” awaits him: we can be in no doubt now that Aeneas is destined for a heroic future. The foreshadowing of the war in Italy also marks the beginning of the transformation of Aeneas’ character from traumatised and reluctant itinerant to victorious military leader and worthy father of Rome.

During his odyssey in the first half of the epic, Aeneas’ meetings with Homeric monsters placed him firmly within the Greek heroic tradition, as he faced up to the grotesque horrors that Greek heroes like Heracles, Odysseus and Theseus have faced before him. In the Underworld, his journey is more personal and profound and his meetings with Palinurus, Dido and Deiphobus see him revisit and make peace with three key periods in his past: his perilous journey as a refugee, his extended delay in Carthage and his former life in Troy. Crucially, Aeneas moves swiftly past each one, a process which is concluded with Deiphobus urging him on towards his future destiny: so Aeneas faces up to his own personal history and is ready to move on, to become reborn as the genitor of the Roman people.

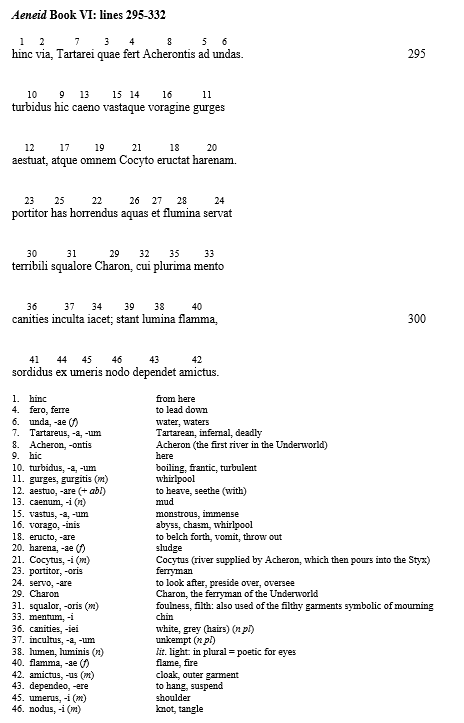

In my archives from back in the day I have lines 295–316 and lines 384–416 produced in the format below. This is just over half the prescription so I am on the scrounge and have already been sent an interlinear translation by Andy James, Head of Classics at Guildford High School, where several of my ex-trainees work. I have sent them my versions of Sagae Thessalae and Pythius in return so it’s a fair swap! The interlinear translation is a really great starting point for me but I do like to provide students with considerably more scaffolding, so I still have work to do: I will probably turn it into a colour-coded text like the one I am using for Sagae Thessalae.

Virgil is a real joy to teach and students respond well to it as a rule. For the last several years I have taught the prose text first as I tend to find that the games Virgil plays with word-order as well as the massive shift towards unfamiliar vocabulary are simply too much for students to cope with; this is working particularly well this year starting with Sagae Thessalae as this particular text contains a significant amount of familiar vocabulary as well as some pretty straightforward grammar that really does not stray far beyond the GCSE language syllabus. The Virgil is always a greater challenge.