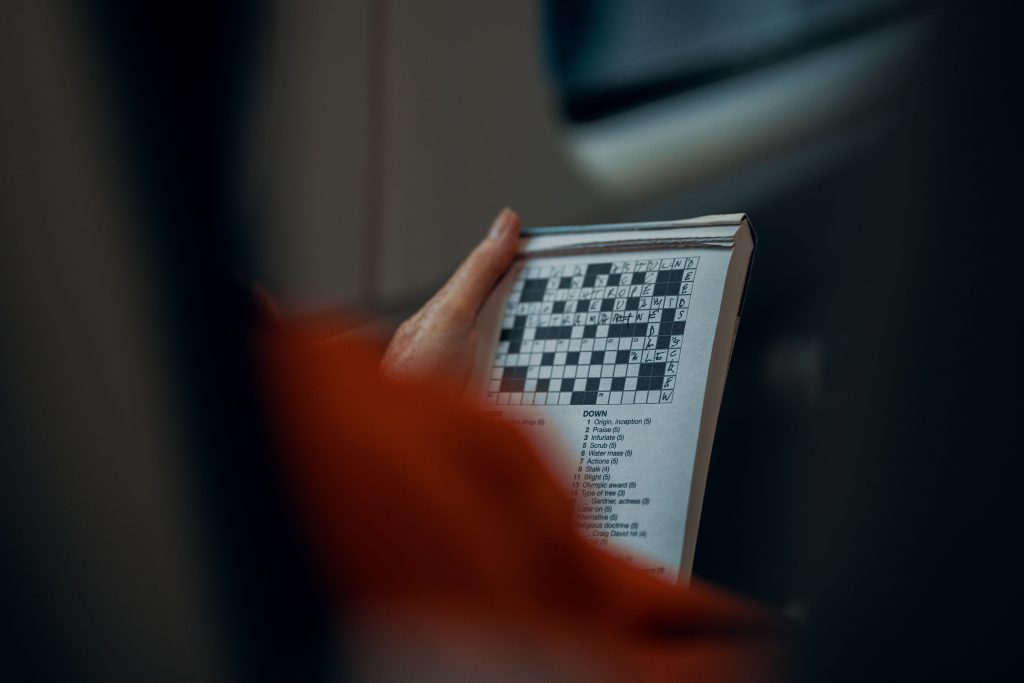

A recent holiday freed up a great deal of my time to spend on some of my hobbies: reading, most particularly listening to audiobooks, and doing the cryptic crossword.

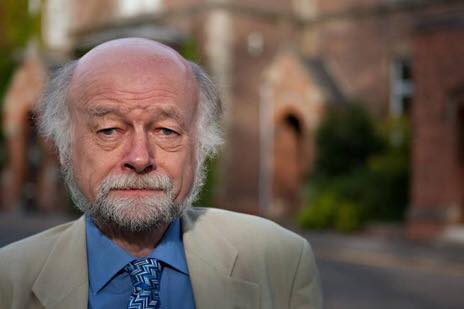

I do not come from a family of cruciverbalists, although my maternal grandather pretended to do the one in the Guardian on most days. My husband was taught the skill at school, believe it or not, by his Latin teacher. This man, who has assumed an almost legendary status among my husband’s old friends, claimed to teach “sailing, golf, bridge and Classics – in that order.” Like many Classicists, he clearly had a magpie brain, and this lends itself to the kind of thinking required to solve crossword puzzles. This particular teacher would usually begin most of his lessons with a crossword clue for students to solve and one of them even went on to become a professional crossword-setter. Not that it pays well, mind you, so don’t quit the day job for it just yet.

I always believed that there was some kind of special intelligence required to do cryptic crosswords and this meant that I avoided them entirely, flapping my hands and saying “oh, my brain just doesn’t work like that”. Like most things, this was learnt behaviour and also stemmed from a basic fear: fear of the unknown and fear of looking stupid. It was only when my husband decided to teach me the rules of the process that I realised that not only was I perfectly capable of tackling cryptic crosswords, I was actually rather good at them.

Some people, I think, do have a natural flair for them and do not require the level of direct instruction that I had to have in order to gain mastery. In a tribute to my husband’s old Classics master, I decided to use his idea of presenting students with the odd cryptic clue during form time. I gradually taught my students some of the rules, but it was striking how a couple of them took to it instinctively from the start. It was also striking how others were convinced they were incapable of it.

Cryptic crosswords require you not take things at face value and some people are indeed naturally good at this type of thinking. Most importantly, crosswords demand that you think deeply about all the possible different meanings of individual words. There are also regular tricks to watch out for that play on either the alternative meaning or an alternative pronunication of a word. Examples would be that “flower” often means “river” (i.e. something that flows) and “in the main” often refers to the sea. “Late” usually means “dead” and “retired” usually connotes a reference to bed, bedtime or sleep rather than turning 65.

On occasion, specialist knowledge of a particular field is required, but there is Google for that: heaven knows how people managed them in the past! Sometimes crossword clues reference Classical themes and I have developed a habit of sharing some of these on my Twitter feed. I have one infuriatingly clever Twitter friend who gets every single clue within 0.8 seconds – this can be particularly disheartening when it’s one that took me 24 hours to solve! But no matter, he is a genius and I am not.

If you’ve ever wondered just how crosswords work, here are a few Classically-themed examples explained below.

The Anglo-French concoction causes amnesia. (5)

For this clue you need to know that whenever a crossword setter says “the French” he usually means le or occasionally la – in other words, “the” in French. In this case, our setter hints that you need the definite article in both English and French. So, you have to combine “the” and “le”. The word “concoction” is a hint that you need to play around with the letters – crossword-setters use a frankly terrifying range of anagram hints which range from the obvious (like this one) to the downright obscure: anything that hints at something being varied, wrong or frankly anything the setter fancies can be an anagram hint. In this case, the anagram only requires you to swap around the words the and le to give you lethe: the name of the river that deceased souls drank from in the Underworld which caused them to forget their past lives. This fits with the definition, which is “amnesia” (forgetfulness).

Some verses provided by exiled poet. (4)

This kind of clue often catches me out. It’s a hidden word, and I have highlighted the answer in bold. Hidden words are most commonly hinted at by the word “some” (as here) but it can also be “in” or “part” or anything similar. Here the setter is hinting that you will find the word hidden somewhere within the words that follow. Ovid was famously exiled by the emperor Augustus for “a poem and a mistake” (we’re not sure what the mistake was!), so the definition is “exiled poet”.

What tourists see in Athens – a harvest on poor soil. (9)

This clue combines three important crossword hacks. Firstly, it’s important not to ignore the little words, especially the indefinite article “a” – in this case, it provides the first letter of the answer. Secondly, you often have to think of an alternative word or synonym for a word that’s given to you. In this case, the synonym for harvest is crop. So far, therefore, we have a-crop– and we’re assuming that the definition is “What tourists see in Athens.” To complete the construction, we have another anagram hint word, which is “poor” – mix up the letters of the word “soil” and you can complete the answer: a-crop-olis: what tourists see in Athens.

“Deploy more reps!” ruled the Romans (8)

My final example indicates just how broad the range of anagram hints can be. In this case, the anagram hint word is “deploy” – it’s telling you to mix up the letters of “more reps” to give you something which can be defined as “ruled the Romans”. Got it yet? E_P_R_R_

Clues in isolation (which is how my husband started to teach me) are actually much more difficult than working on a whole puzzle – once you break into a crossword, that gives you some letters to play with, as I did for you at the end of the previous paragraph. When I first started I would look up some key long answers to give me some letters so I could get going. Three years on, I still continue to look up every answer I can’t deduce to see if I can explain it. If I can’t work out why the answer is what it is, I ask my husband; if he can’t work it out I ask his friends! It is rare for me to find a clue that nobody in our circle can explain, although it does sometimes happen!