Latin has something of a reputation. Everyone thinks it’s difficult and indeed it is. But so is mathematics and so is any language once you get beyond “bonjour, je m’appelle Alain”. Grammar is difficult and still not explicitly taught in our own language to the degree that it is in many other countries.

So why do some children struggle with Latin over and above anything else?

One reason is the unfamiliar territory that the language presents to family and friends. Many parents and guardians feel able to offer some kind of support to their children in the majority of subjects, certainly in the early years. I work with many families who are thoroughly involved when it comes to the children’s homework and it’s true that many children benefit from adult support in their studies at home – during lockdown, this took on a whole new importance. Lots of families employ me because they care about their children’s studies and feel ill-equipped to support them due to their own lack of knowledge, and with only around two and a half percent of state schools currently offering Latin on their timetable, I don’t anticipate the situation changing in a hurry. As a result of the fact that so few people have any experience of Latin as a subject, it maintains a certain mystique, all feeding into its reputation for being inaccessible and challenging.

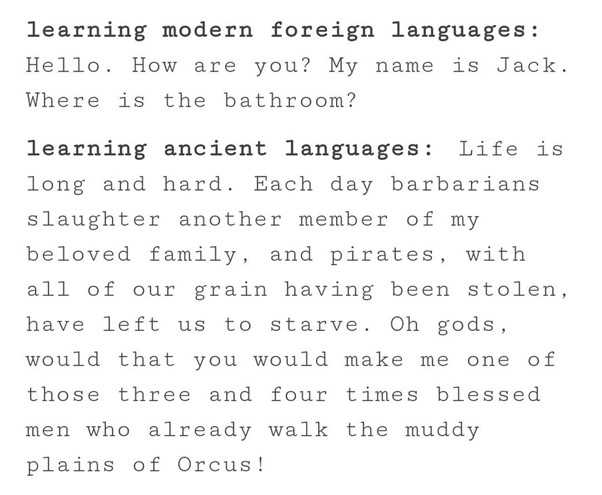

Furthermore, and at the risk of stating the obvious, Latin is an ancient language – and a dead one. What that means quite simply is that nobody speaks it any more. As a result, the content of what you are translating will often seem obscure to you, due to the fact that the world has changed rather a lot. The ancient world was very different from ours and much of what went on even in the most mundane aspects of daily life can seem unfamiliar or even bizarre. Add to this the fact that a lot of the time students will be looking at stories from ancient myths or founding legends and we’re in a whole new world of weirdness. This inescapable fact is captured rather brilliantly in this little meme, which has been circulating the internet for as long as I can remember:

The thing is, children generally like the weirdness and indeed the darkness. If you think that youngsters don’t like dark stories then explain the thundering success of an author such as Patrick Ness. Generally, children are not put off by the puzzling nature of what they are translating; but it certainly can contribute to their belief that the material is obscure.

So, we’ve dealt with Latin’s reputation and we’ve established that the inherent fact of it being an ancient, dead language may make it potentially difficult to access. On top of that lies the inesecapable fact that Latin as a language is very different from our own. The most important thing to understand about Latin is that it is a heavily inflected language. This means that word formation matters, but we’re not just talking about spelling here: we’re talking about the fact that the very meaning of a word is adjusted by its formation. In inflected languages, words are modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, voice, number, gender and mood. The inflection of verbs is called conjugation and this will be familiar to students of all languages. However, in Latin (and in other heavily inflected languages such as German) nouns are inflected too, as are adjectives, participles, pronouns and some numerals. The inflection of nouns is called declension.

What blows students’ minds the most, in my experience, is how this inflection translates into English and how the rendering of that translation can be confusing. For example ad feminam means “to the woman” but in the sense of “going towards”. I might use it in a sentence such as “the boy ran over to the woman”. However, feminae can also mean “to the woman”, but this time in the sense of giving something to: so I might use it in a sentence such as “I gave a gift to the woman”. And that’s before we’ve even explored the fact that we also use the word “to” when forming our infinitive “e.g. “the woman likes to run”). Trying to unpick why grammatically different concepts sound the same in English is just one tiny example of a myriad of misconceptions that children can be carrying around in their own head.

Misunderstandings can arise everywhere. Imagine I’m in front of a class and I say “the dative case can be translated as “to” or “for” in English. Pretty clear, right? But if you were hearing a teacher say this rather than reading it, I wonder if you might have heard “the dative case can be translated as “two” or “four” in English.” I discovered this misconception once and it exemplifies perfectly why dual coding (providing a visual representation of what you are explaining, ideally formed in real time) is essential when it comes to grammatical explanations. What’s great about one-to-one tutoring is these kinds of misconceptions can be uncovered and rectified.

Due to its inflection, many Latin words can be difficult to recognise as they decline or conjugate, and this brings us to what many students can find the most disheartening aspect of the subject: vocabulary learning. If a student has worked hard to learn the meaning of a list of words, imagine their disappointment and frustration when this effort bears no fruit for them. A child may have learnt that “do” means “give”. Yet will they recognise “dant”, “dabamus” or “dederunt” as parts of the same verb? Without explicit instruction and support, probably not. This can be really depressing for students and can result in them giving up altogether. It’s also why parental support with vocabulary learning can only take a student so far. That’s where a tutor can help.

Furthermore, due to the inflection of the language, a Latin sentence has to be “decoded” rather than read from left to right – breaking the habit of reading from left to right is something I have written about before and it is without a doubt one of the biggest barriers to students’ progress in my experience. Working on this and supporting students with their ability to tackle each Latin sentence in the right way forms much of what I do as a tutor. Even when a child has worked hard to learn all of their noun endings and all of their verb endings, they still need a huge amount of support and scaffolding to show them how to process these and map them onto what they are translating.

I remain unsure whether Latin really is any harder than any other subject. I believe that its reputation is mainly to do with the fact of its obscurity and how few people have the ability to access it. While this remains the case, however, the demand for support and tutoring will always be high.