As an avid reader of fiction, I have a problem. It’s a wonderful problem to have, and illustrates the many and various ways in which the modern world can be truly wonderful. My problem is keeping track of what I’ve read.

Were I not to do so, I’d be in an infinite loop of doubt: “Have I read this?” The feeling can begin at any time: when I look at the cover of a book, read the blurb, hear the name of the author or – perhaps most discombobulating of all – when I’m part way through the book. You might think it shouldn’t matter, but there is a tiny part of me that is undeniably anxious about the number of books that there are in the world and the ever- diminishing time I have available to read them. Accidentally repeating the exercise with one of them sets off the same kind of first-world anxiety that lots of people experience when they realise that they’re not wearing their FitBit when they’re half way through their daily run. That voice in your head that says, this doesn’t count towards my target!

Before I discuss the thorny solution to my problem, I would just like to pause and celebrate the sheer joy that this “problem” exists. When I was a child, and perhaps even more of a booklover than I am now, I used to have a fantasy that I could close my eyes, open my palms and the perfect book for that moment would appear. Since the advent of digital technology exploded into the publishing world, this fantasy is now a concrete, daily reality. I can order a book and – milliseconds later – I can be reading it. The advent of the Kindle and similar devices, followed rapidly by the spectacular surge in the audiobook industry, has made books and their contents more accessible than ever. It enables reading on the go, reading while you’re working on mindless chores that would otherwise be soul-destroying and reading in an instant. It is not only accessible but increasingly affordable. As well as the remarkably affordable global phenomenon that is Amazon that shook the market to its core, there are millions of electronic books and audiobooks available through the library for free and I absolutely love it. I cannot stress enough how utterly glorious this literary digital revolution has been for me, especially as someone with ropey eyesight.

Right – back to whingeing.

To solve the problem I have, which – if you recall – is keeping track of what I’ve read, for many years I have turned to recording what I’ve read on a site called GoodReads. It is by far the biggest and most successful platform of its kind, and like all social media platforms it began as a wonderful idea. A community of booklovers, coming together online, on a platform that exploits all the modern benefits of social media but focuses entirely on books – recommendations, reviews, suggestions and comments. Sounds wonderful doesn’t it? What’s not to like? Well, like most social media platforms, there is unfortunately quite a lot not to like.

Since its launch in 2006, GoodReads has become increasingly dominated by a certain kind of reader. I hesitate to label them as belonging to a particular generation, as I’m not sure it’s that simple, but these readers are the ones who see everything that has ever been written as “problematic”. Ever in search of reasons to be offended, they trawl the corpus of modern and classic fiction, hunting for dissent from their tribal causes of righteousness and sniffing out any indication of a worldview that may jar with their own, even if that worldview is expressed by a fictional character.

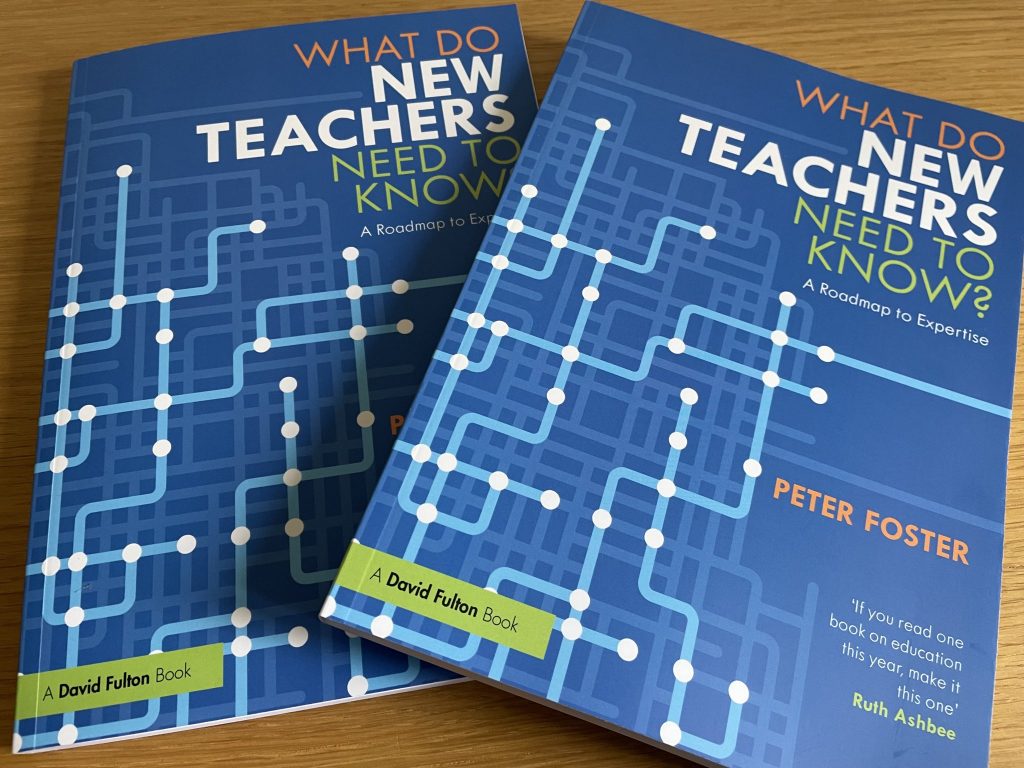

It must be a truly exhausting existence, especially if you want to read anything written prior to the 21st century, which can be a challenge for all of us who have been steeped in modern liberalism. A few years ago, I read Down and Out in Paris and London by George Orwell and found myself positively wincing at his choice of language. Similarly, it’s been an education to dip into some Agatha Christie and discover the casual classicism and a truly profound contempt for her own sex. This all jars with modern values and if you’re normally a reader of contemporary fiction it can come as quite a surprise. I would happily support a review of such books which said something like, “remember, this book was written around 80 years ago, so the attitudes and views expressed will not reflect 21st century values”. That is all that needs to be said, a trigger warning for the ineluctably stupid who need it pointing out to them that people in the past didn’t necessarily think the same as we do. If you really want to blow their minds, try asking them what 22nd century humans will think of their own prejudices; they won’t be able to think of any, because that’s how prejudice works: it’s only obvious when you look back at it.

You’re probably thinking I should give you a couple of examples of the GoodReads phenomenon. Okay. According to the good folk of GoodReads, a Young Adult novel that I enjoyed as a teenager is officially racist because it’s a fantasy novel about astral projection, which is the ability to remove your soul from your own body, and this is (apparently) cultural appropriation from the native Americans. Honest to God, there are people losing their minds over whether the supposed ability to teleport your soul around the world is racist. Some readers lay into the same novel being “sizeist” as well, and I have to say I have absolutely zero recollection of that in the novel. Similarly, there are hundreds of people claiming that Lionel Shriver (she of We Need to Talk About Kevin fame) can’t write, because her recent novel about tone-policing in society is just a little too close to the bone for them. “I feel like if you’re going to try and do Orwell in 2024, you have to try and write at least as well as Orwell” snipes one, whilst in the next beat admitting “I’m not much of a fan of Orwell.” That one genuinely made me hoot. Less so the one filled with expletives that describes Shriver as nothing more than “a well-off, educated white woman” – the ultimate modern-day insult.

I have searched for a better option and there does not appear to be one, so GoodReads is where I’m stuck. The algorithms are useful, in a way that they are not when it comes to other products available for purchase. If I’ve just bought a new dishwasher, then I’m not interested in suggestions for other dishwashers. However, if I’ve just enjoyed a rip-roaring thriller about zombies, I am more than open to suggestions for similar rip-roaring thrillers about zombies, so GoodReads has some value through its automated suggestions. As for the humans that populate the site, I shall endeavour to do my best to avoid their opinions and their tone-policing. I hate to say it, but for once I’d rather listen to the computer.