The toe-curling indignity of Joe Biden’s current situation is a lesson to us all. A lesson in what happens when a system favours old guys and then wonders why those old guys won’t move over when it’s time. A system that appears not to have considered what might happen if it’s desperately obvious that one of those old guys should take a back seat, but the dude wants to stay behind the wheel. A system so unwieldy and expensive that the only people who can afford to play the game are – as a general rule – those same old white guys, the ones who don’t want to take their hands off the wheel.

How does anybody know when it’s time to stop? Biden’s painful crumbling in front of the world has reminded me how as a youngster I promised myself fiercely that I would know when my time was done. To me, this does not just apply to when it’s time to retire, but throughout your career when you’re done with a particular role. Whatever I took on in education, I gave it my best shot and then handed it over. I made whatever changes I felt were needed, led people and adjusted systems to what I felt worked best, but always handed over the role when I had run out of ideas. Every. Single. Time. Quite literally my worst nightmare was the idea that people were saying behind my back “why doesn’t she just go?” The thought genuinely filled me with dread. Happily, due to my overwhelming desire to avoid this situation, I’m pretty sure it’s never happened.

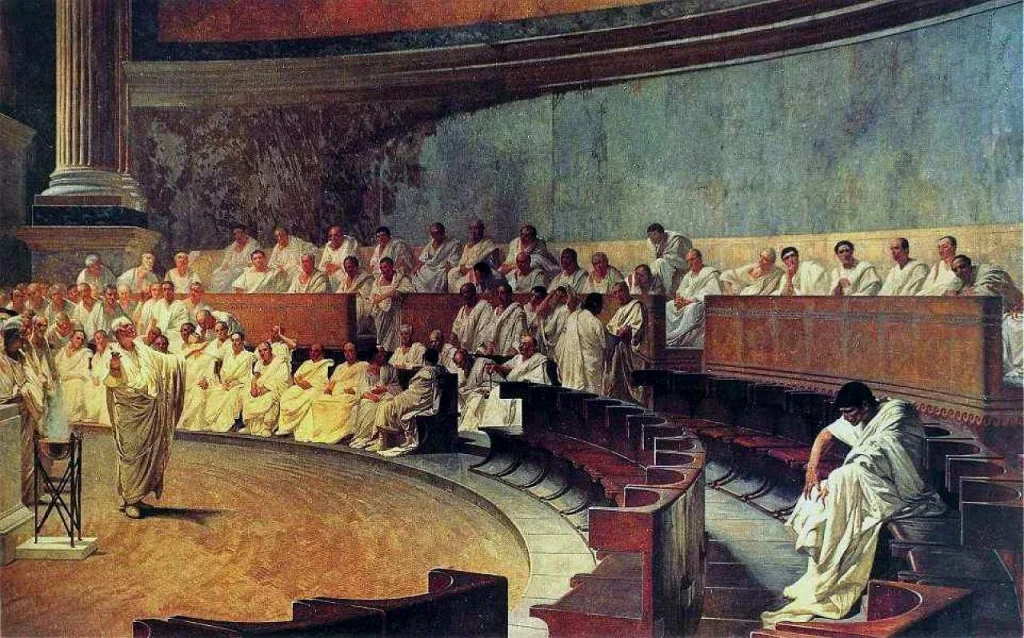

On this side of the Atlantic, whatever your politics, I think it’s fair to say that our outgoing government was running out of ideas. Our system is based on a pattern of rotation, ensuring that nobody gets too stale in their role: when a cabinet and the government in general is fresh out of new proposals, we vote them out. The whole process runs on a cycle and – broadly speaking – it works for the best. Only the most partisan (and those who haven’t lived very long) really believe that seismic change will come with a change of government, but everyone can get behind the idea that a fresh line of buttocks on seats in the cabinet office can only be a good thing. Time for something different, for those who are not worn down by cynicism to give it a go. Nothing could be more true this time, when it’s fair to say that the outgoing government has had some issues.

Although not a great follower of any kind of sport, I did smile to myself this time last year when the 20-year-old Carlos Alcaraz smashed Novak Djokovic’s bid for his 8th Wimbledon title. You see, however outstanding you are in your field, there will always be the next youngster snapping at your heels. That’s just as it should be. Personally, I find it inspiring and comforting that there is always somebody coming up through the ranks that is likely to do your job better than you did. I do not find this a threat. I am at peace with the contribution that I made at the chalkface and continue to make as a tutor in extremely high demand – experience counts. But I am genuinely delighted to have met the next person who will be doing my old job in the comprehensive school I left two years ago and to find that she is enthusiastic, passionate and bursting with ideas. Nothing would give me more joy than to see the role flourish and grow. It is not my possession, it is my legacy – and a legacy only works when there are new people keen to do something even better than you did.

Will Biden finally realise that it’s time to step back and spend more time on his sofa – one that isn’t in the Oval office? One can only hope that he is surrounded by advisors with courage, not the usual troupe of sycophants that great world leaders tend to find themselves hemmed in by. Will he listen? The message seems to be that it’s unlikely. The strongest and best leaders I have ever known are the ones who listen to the things they do not want to hear. As someone who is quite good at opening their mouth when others tend to keep theirs closed, I have often found myself to be the reluctant Cassandra in the room. In my experience, the best leaders will listen, nod and thank you for having the gumption to challenge them. The worst will destroy you for speaking the truth. Quite how and why the Democrats have ended up in this position is for those who understand US politics in depth to explain, but I suspect that it’s inertia that has brought them here. Nothing is worse than doing things as they’ve always been done for no other reason than the fact that they’ve always been done that way. Presidents always run for a second term, even if they’re in their 80s and showing clear signs of deterioration despite the best healthcare that their capacious wallet can buy.