As a career-long devotee of the OCR specification, for various reasons it is time for me to get to grips with the Eduqas (WJEC) specification. I am aware that my successor at the large comprehensive I used to work in is going to switch to WJEC and given that A level Latin is no longer available in our area (unless you go private) I fully support his decision and would have taken it myself. For my own part I’d like to be able to offer support to students taking both specifications, plus a home-schooled boy I am working with now will – I believe – respond much better to the WJEC course.

Given my need to concentrate on the finer details of the differences between a specification that is new to me and one which I know like the back of my hand, I decided to focus my mind by writing up my findings in a blog post. There’s nothing like having to explain something in your own words to make one concentrate. This is, by the way, a recognised truth when it comes to learning: simply reading something or even taking notes from a source is unlikely to aid your understanding. Putting your source to one side and then trying to explain it in your own words has been proven to be a much more powerful way to ensure that you will remember what you are studying. This is because our memory is reconstructive rather than reproductive; memory works (and therefore improves) by continuously regenerating what it remembers, so forcing yourself to reproduce in your own words something you’ve read about is a challenging but effective way to ensure that your newfound knowledge will stick.

So, here are my findings. If you’re interested in the full range of qualifications available in all Classical subjects at all levels in the UK, Steven Hunt provides a really useful overview in a 2020 article for the CUCD, which is publicly available. He discusses the specifications available for A level, the IB and beyond.

General overview

A GCSE qualification in Latin and accredited by OfQual for use in English state schools is offered by OCR and by Eduqas, which is the examining body of WJEC accredited for use in England. AQA used to offer a GCSE in Latin but this was discontinued before the new GCSEs were launched in 2018. Both OCR and WJEC have shared criteria, which are dictated to them by OfQual: the number of examination papers (three) and the length of those papers, the minimum length of the literature that must be studied in the original Latin (around 200 lines), plus a choice between an element of prose composition or questions on grammar and syntax. There is no coursework or controlled assessment and the examination must be linear, not modular – in other words, it must be sat as a series of final examinations at the end of the course. Despite these prescriptions, the two examination boards still provide some considerable variation, which I examine below.

Compulsory language paper

The language paper, compulsory in both specifications, lasts for an hour and a half and makes up 50% of both qualfications. Both specifications have a set vocabulary list and both of them state that students will be tested through translation and comprehension, plus a choice between some grammar questiona and some short prose-composition sentences (for which there is a restricted vocabulary list and a restricted grammar list). Both boards test students’ knowledge of the accidence and syntax laid out in their specifications and this is where the differences lie: the demands placed on students by the WJEC language specification are notably lighter than those expected by OCR.

Both specifications call for a knowledge of all five declensions – in reality, this means a focus on declensions 1-3, as the words from the defined vocabulary list in the 4th and 5th declension are vanishingly few. Similarly, both specifications expect a knowledge of all forms of adjectives, including their comparatives and superlatives. However, there is considerable difference between the two boards when it comes to a knowledge of verbs and all their derivative forms: OCR theoretically demands the indicative forms of regular and deponent verbs in all voices and tenses except for the future perfect; in the subjunctive it requires the impefect and the pluperfect. WJEC, when it comes to the passive voice and deponents, demands only the present, imperfect and perfect passive and deponent verbs in the 3rd person indicative! I had to read this several times to make sure I was reading it right. So, no pluperfect passive and no passives of any kind in the subjunctive and they will only need to recognise passive and deponent verbs in the 3rd person. When it comes to the syntax, the basic uses of the subjunctive seem to be identical with the expectations of OCR.

Participles? OCR expect the lot, whereas WJEC do not list the future participle as an expectation. They also state – and brace yourself here, if you’re an advocate of the OCR syllabus – that the ablative absolute is not required. I am still reeling from this. No ablative absolute. I mean … wow. It goes on. Another shock came when I realised that WJEC only expect students to recognise the present active infinitive – no others. This means that their testing of the indirect statement will be very basic and the relevant rules for the sequence of tenses will be very easy to teach.

Other smaller differences in the expectations for the language paper remain, such as WJEC does not include malo in its list of irregular verbs, unlike OCR. Likewise, the verbs sum and possum are only required in the present and imperfect indicative, present infinitive and imperfect subjunctive for WJEC. These differences may seem minor but in reality it means that there is a massive stack of knowledge not required by WJEC. The fact that students end up with the same qualification does give me pause, and were I teaching with the aim of preparing students for A level then I would stick with OCR. However, with the removal of A level as an option in my local area then my successor’s decision to switch to WJEC is entirely correct: it would almost be madness to do otherwise.

Literature and culture: with options:

The boards differ further in the way they lay out their literature and culture papers. For OCR, candidates must be prepared for two out of the following three options, each worth 25%: prose set text, verse set text or Roman literature and culture in translation. This means that all candidates must study one text of around 200 lines in the original language, and many will study two. Personally, I always taught both set texts as I hated the vagaries of “just teach them some stuff about slavery/daily life”.

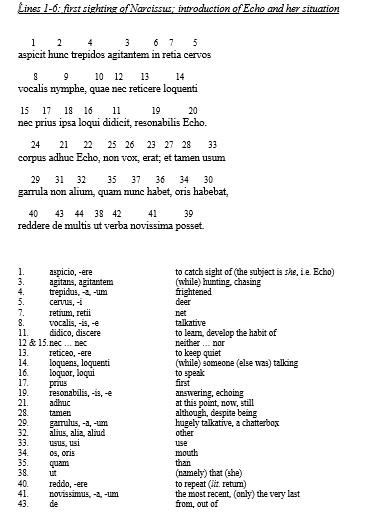

WJEC lays things out a little differently. Their “Latin literature: themes and sources” paper is compulsory and worth 20%. Teachers have a choice of theme but whichever they choose consists of a mix of both prose and verse texts in the original language. There is also some supporting material, which is designed to place the texts in their cultural context. For the final paper, worth 30%, teachers can choose to prepare their students for “Latin literature narratives”(basically more set text work, mostly in the original with some sections in translation), or they can choose the “Roman civilisation” element, in which students study some general themes and sources all in translation. Personally, I will be avoiding that for the same reasons as I avoided the cultural background paper with OCR.

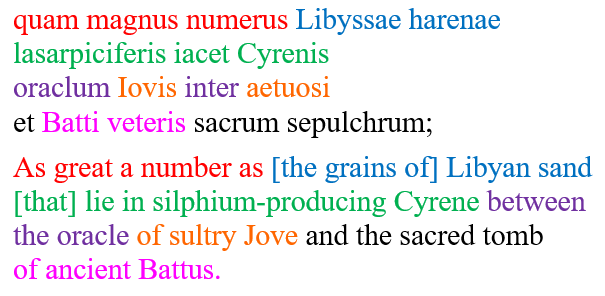

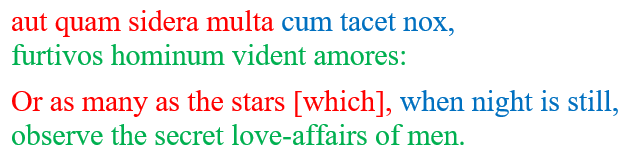

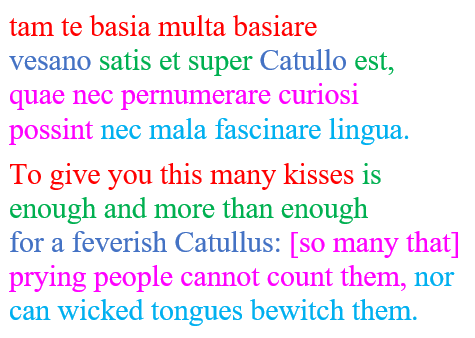

A key difference in approach to the literature between the two boards is that OCR literature examinations are closed book, which means that the students need to know the texts really well – frankly, they need to know them off by heart. WJEC take a rather different approach by making their examinations open book, meaning that students are provided with a clean copy of the Latin text plus the vocabulary list. In terms of teacher preparation and school investment, the very fact that WJEC provide the the texts and the vocabulary online as a PDF download is in itself quite a revelation – OCR leave you to get on with it all by yourself. That said, there is no set translation provided, so teachers will still need to prepare their own working translation and/or one for their students.

I am keen to reach out to teachers who are more experienced in preparing their students for the WJEC literature as I am as yet unsure how much they feel their students should rely on the texts in the examination. Something I recall from doing open-book examinations back when I sat my A levels is that you really don’t have time to be looking too many things up, so in reality you still needed to know the text like the back of your hand. I am also not sure how much advantage it will give students when the text is all in Latin; surely they still need to know a translation really well, since none of them will be truly capable of translating real Latin on sight (especially if they haven’t studied the OCR language specification!)

So, my mission now is to do so and start making as many friends as I can with the WJEC advocates. I am looking forward to the process. I am also excited about the prospect of working with different texts and I like WJEC’s decision to include supporting material, which forces teachers to contenxtualise the texts for their students; OCR’s approach encourages robotic rote-learning, which always felt like something of a shame. So, calling all teachers of WJEC – where are you? I’d love to learn from you.