Just occasionally, a student will say something so extraordinary that I am stopped in my tracks. This week, it was when a child I have been working with in the run-up to her GCSE examinations told me that she had to resort to writing on her hand during a lesson.

I was hesitant to write this piece, for it means going over ground I have covered before; but in the spirit in which this blog was started, I remain committed to writing about what is on my mind at the time, and this week I am haunted by the fact that a student was unable to write down a question during her lesson.

More and more schools in the private sector have moved to a digital model, in which lessons are conducted using tablets or – most commonly – Chromebooks. I am deeply suspicious that this is a money-saving exercise, since schools can access the equipment at a considerable discount when buying in bulk, and anyone who has seen the average photocopying budget for a busy department will come to realise that the potential saving is considerable, once the initial investment is made. Printing booklets is expensive, and this fact seems to be outweighing the fact that they are effective learning tools.

The young people I work with are – as one might expect – reasonably tech savvy, but they are universally scathing about their school’s digital approach. Without exception, they report that the technology is clumsy, unreliable and not fit for purpose. They will even volunteer the fact that it is distracting and hampers learning by offering up temptations that would otherwise not be present. Students report a quite extraordinary litany of what they get up to on their laptops when they are meant to be on task during a lesson: at best, they may be doing homework for another subject; at worst, they will be playing games or accessing chat applications. All of them agree that they cannot discern what tangible positives the technology brings to their learning. Moreover, as I discussed at greater length back in January, they lack the skills and the maturity to manage their learning through digital platforms. Organising, managing and accessing large files and using screen-splitting to make this viable is genuinely beyond a significant number of students: frankly, it’s beyond a lot of adults.

So far, so predictable. The student I spoke to this week has been one of the many who have expressed frustration with her school’s digital approach and has found it difficult to access her notes and prior learning. There are constructions she has no recollection of ever been taught, which is not uncommon, but what is concerning is the fact that she cannot find a way to revisit her own notes on the topic. Had the school been using a well-organised printed booklet, this would have been effortless. Once again, the technology is working against her, which pretty much undermines everything that technology is meant to stand for; technology should be a facilitator and an enabler, not a barrier to learning.

I really struggle to comprehend why so many schools have switched to a digital model, despite the overwhelming evidence that handwriting is better for cognition. Handwriting engages a broader network of brain regions and motor skills compared to typing, potentially leading to better memory formation and learning. Typing is faster and more efficient when it comes to output, but it involves less active cognitive engagement and thus fewer opportunities for memory consolidation. Typing is fantastic for fast communication – it is not so for learning. Writing by hand forces the brain to engage in a more active, sensory-motor experience; the process activates the regions in the brain responsible for motor control, visual processing, and sensory input – a much broader range than is required for typing. Studies have shown that handwriting leads to more elaborate and widespread brain connectivity patterns than typing, suggesting that the act of writing by hand is thus more effective for encoding new information and forming memories. This is why, when I am learning something off by heart, I don’t do it (exclusively) on the computer.

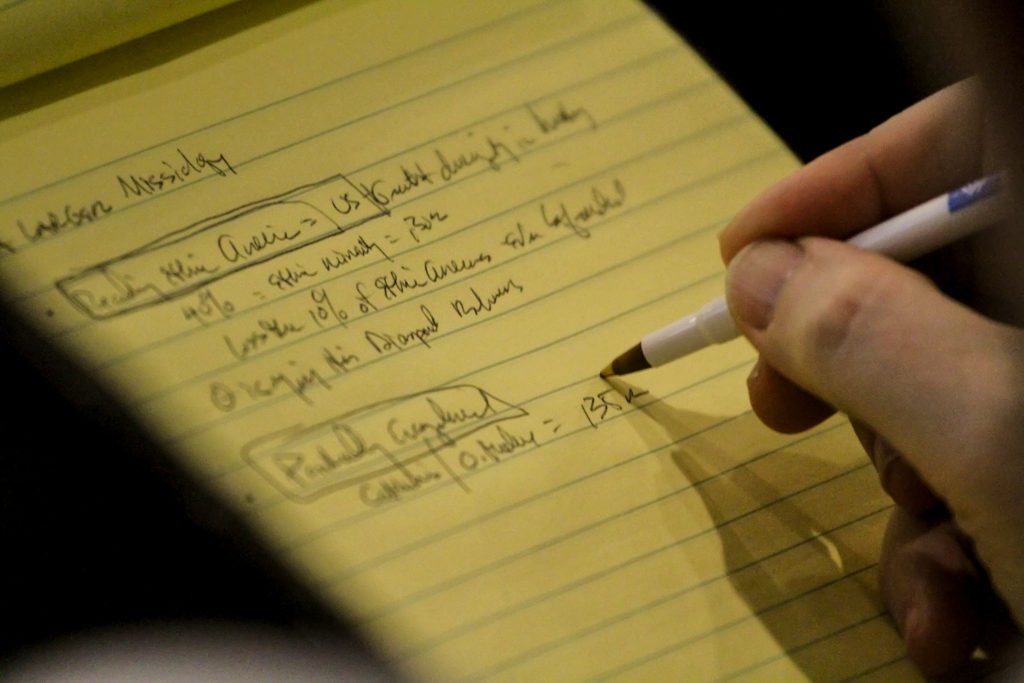

But aside from all of this, let’s just think of the practicalities. I am a huge fan of technology and I do pretty much everything through it. I use a digital calendar, as I find it more effective and efficient than a traditional one. All my tutoring is online, so all the resources I use with students are presentable on screen. However, when I send them resources, these are almost always designed to be printed out and held in their hands. In addition, and here’s what is most relevant to my post today, I have a lined pad beside my laptop for notes. When a student asks me to send them something after the session, I jot that down on the notepad. When a student warns me that they will be able to make the next session, I jot that down on the notepad. It is simply more efficient and quicker to do this than to open a file and make a note in a corner of my digital resources. The notepad sits beside me at all times and I cross off each note as I implement it. The page beside me as I type has the following written down and crossed through (names have been changed):

Billy – noun table

Olivia – YouTube vid. on 10-markers

Niall – 2021 paper + Rome qus

This is exactly the kind of thing that a notepad is needed for – quick notes to self that will be implemented immediately and ticked off. There is no need for a permanent record, just a requirement for an immediate visual reminder to action something at the end of my run of sessions. None of this is rocket science, or so I thought.

Yesterday, when my student reported that she had some questions arising from her first lesson back in school, she admitted that she was struggling to remember them because she had not been able to write them down. Not only has her school moved so entirely over to Chromebooks that students appear not to have any kind of papers, notebooks or diaries to hand, but get this: her teacher seems aware of the fact that the Chromebooks are causing distraction during the lesson, so has banned students from accessing them during the lesson. This would be fine if the students were given an alternative route to note-taking, but that’s presumably against whole-school policy, so instead the students are left with nothing to write on. “So, I wrote it on my hand,” she said, “but then I couldn’t make it out and it got washed off later in the day.”

So, there we have it. What a stunning victory for technology over common sense. You have a child left unable to access her notes, unable to write down a question for their teacher or tutor (the fact that she wanted to save a question for one-to-one time rather than interrupting the flow of the lesson should surely be applauded) and a piece of technology which undermines learning to such an extent that the teacher is forced to discontinue its use in lessons without a suitable replacement. Three cheers for our ability to make the world just a little bit more bonkers than it needs to be.