tempora mutantur, nos et mutamur in illis

For those of us whose lives are tied up with education, the academic year can be a far more powerful marker of the changing times than the winter solstice.

I have always found the gateway to January a strange thing to celebrate, yet the pressure you’re under to party like it’s 1999 on December 31st is relentless. Fast-forward 24 hours and suddenly everyone is on a detox, which is even more depressing: count me out on that one – as if January weren’t miserable enough! January is – without a doubt – the most intolerable month of the year. Long. Cold. Dark. Simply awful. One of my oldest friends has a birthday in the first week of January and she tells me it’s agony. Quite literally, nobody wants to know; everyone battens down the hatches and goes into hibernation when it comes to socialising. It’s a month to be endured, not enjoyed.

September 1st is the New Year for me – always has been. As someone who has never left education, my year has been shaped by the academic calendar for as long as I can remember. I left school for university, stayed there far longer than is decent and then went into a PGCE followed by full-time teaching. I have quite literally never seen the world when it has not been shaped by academic term times and academic holidays. So as the days start to shorten at the end of August, quite strikingly in that final week, it’s as if the world is preparing itself: ah yes, I think, time to sharpen the pencils and prepare the rucksack. Season of lists and hello brutalness: it’s back to the chalkface again.

This year, of course, feels somewhat different for me, and today is particularly symbolic. Today the local school I used to work at opens its doors to staff and welcomes them back for two INSET days prior to students returning on Monday: many schools across the country are following a similar pattern. For the first time in 21 years I will not be there. So what will I be doing? I have a couple of clients in the morning, one child who – like most – is not yet back in school plus a regular adult client. After that – and just because I can – I’ll be going into London to meet an old friend for lunch. Cheers!

I won’t miss the hard plastic chairs and the “vision” for the next five years. I won’t miss the results analysis. I won’t miss the overwhelming feeling that my time could be better spent preparing my classroom and writing my seating plans. I will miss the people, the camaraderie, the sense of belonging. I knew it would be this way: the price we pay for opting out of any system, for jumping off the hamster wheel, is a slight sense of wistfulness as we watch the other hamsters do their scampering. It’s still worth it.

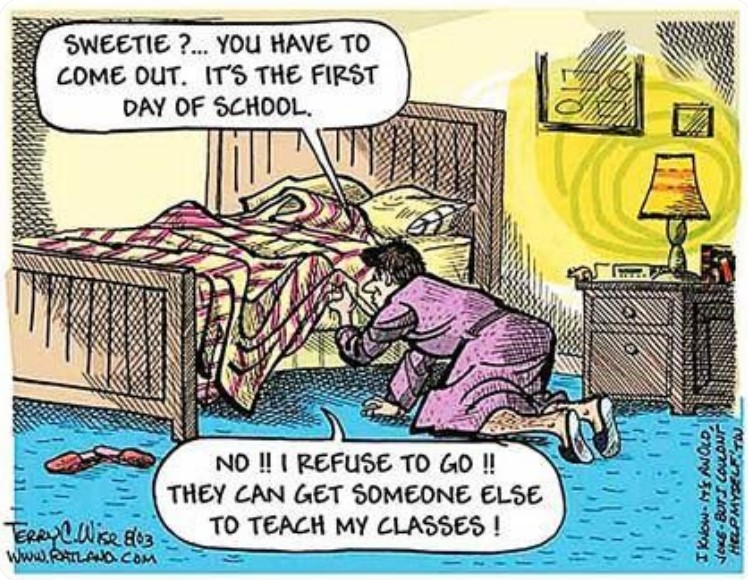

For many teachers, the start of September is marred by anxiety dreams. Many teachers love their job, but this does not make them immune to feelings of apprehension when it’s time to go back to school. Six weeks is a long time away from a job which relies so much on performance and – like any performer – teachers are often plagued with self-doubt prior to their return to the stage. My most common recurring dream is being in front of a class which will simply not listen; I stand impotently at the front, wringing my hands, snapping at the children who either talk over me or laugh. There have been times when I have woken myself up shouting. Strangely enough (or perhaps it’s not so strange) I have still had a couple of these anxiety dreams this year; my subconscious has clearly not absorbed the fact that I will not be returning to the chalkface and is still convinced that I will find myself in front of a class next week; given that I still occasionally have an anxiety dream about completing my PhD – something which I did in 1999 – I’m not holding my breath for when these dreams will stop.

Teaching is a wonderful job in a thousand ways and while the end of the summer holiday was always a bit of a drag (as my husband puts it: fundamentally, work sucks) I did still look forward to the start of the new year in September. There was something wonderful about the fresh start and the preparation for the return of old students and the welcoming of the new. Each year I strived to do a better job than the last and each year – in incremental ways – I believe I managed it.

This year for me brings greater excitement though, as I step into my new guise as professional Latin tutor and start shaping my business for the academic year. The summer is a tricky time for tutors, with many families choosing to take the whole holiday away from the books; despite this, I have been pleasantly surprised by the amount of work that has come my way, with several new clients booking in for summer booster sessions and others wishing to make a head-start on their studies for the new academic year. I have an encouraging number of new clients booked in from next week and my weekend slots are already close to full for the year – something I could not have imagined happening so quickly.

So to mark the beginning of the academic year I shall be raising a glass to my colleagues and thinking of the scores of friends I have stepping back up to the chalkface once again. Like me, many of them truly love it, but also like me, many of them have found the last couple of years the toughest since the start of their career. I hope things get better for them. I hope the press and the government cut them some slack for once. I hope OfSted don’t come calling until they’ve at least got into the swing of things once more. I hope they’re able and allowed to turn the heating on when they need it. I hope the students know how lucky they are.