Has your teenager ever assured you that they are great at multi-tasking? Or have you heard it said that the younger generation, because they have grown up in a multi-media world, are great at multitasking? Well, I’ve got news for you and for your teenager: I’m afraid it isn’t true.

First of all, whatever people may tell you, research tells us that multi-tasking is a myth. What humans are doing when they multi-task is – in fact – constantly switching their attention between two things. It is undeniable that some people seem to find this easier (or perhaps one should say that they find it less stressful or irritating) than others; but the idea that anyone can pay full attention to two different things at the same time is a fallacy – and yes, I’m afraid that goes for girls as well as boys! A study by the University of London found that participants who “multi-tasked” during cognitive tests underwent a decline in performance similar to participants who has stayed up all night; some of the adults participating in the test saw their IQ drop by 15 points, leaving them with the average IQ of an 8-year-old child.

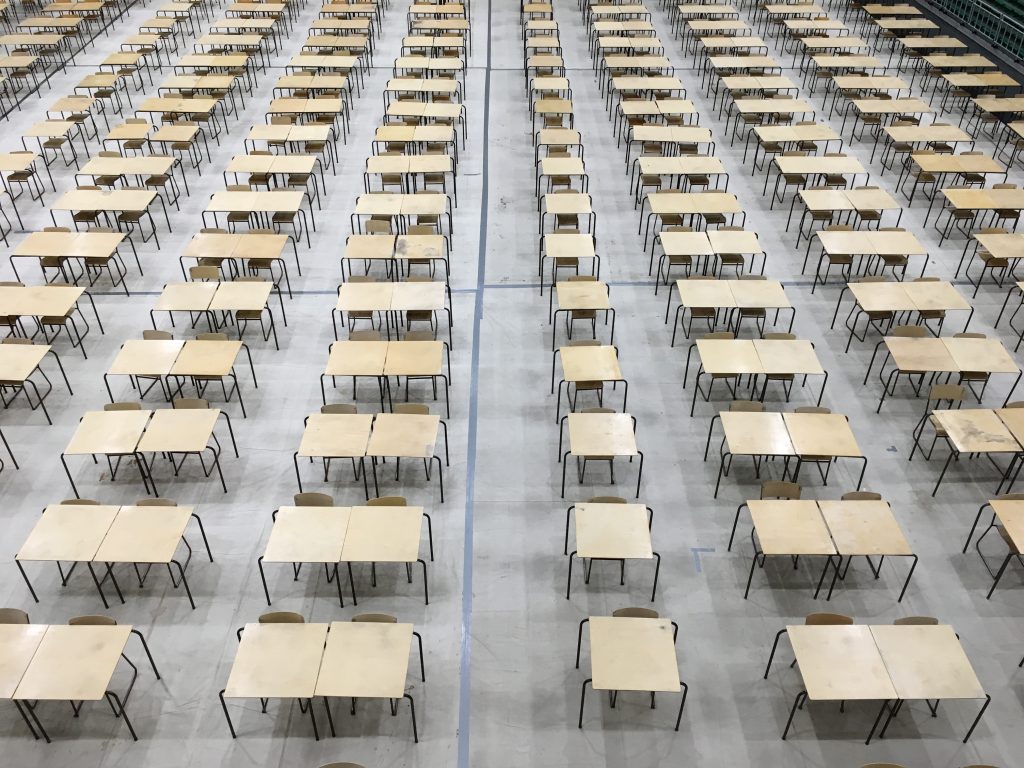

The fact that multi-tasking is a myth has been known by cognitive scientists for some time, and is one of the main reasons why working in silence when concentrating on a difficult task is so important, both in school and in private study. Peripheral noise, including both chatter and music, is distracting to the brain and will impair cognitive performance. If our concentration is interrupted by noise the brain starts to become overloaded, with more senses being alerted and more thought patterns therefore fighting for our focus. For people working in busy environments, noise can put a real stress on the brain, affecting people’s ability to work at anything like their full capacity. While many people may feel they have adapted to working in noisy environments, the research indicates that this is far from ideal when it comes to congitive performance, and therefore far from ideal when studying. A study published in Psychological Science found that children exposed to excessive noise in their school environment are more likely to suffer from stress than children who are educated in quieter areas; the study indicated that students who attended schools located near airports had significantly higher levels of the stress hormones (adrenaline and cortisol) as well as markedly higher blood-pressure.

But it’s not just unpleasant or unwanted noise that can cause a problem. Has your teenager ever told you that they need to listen to music while they work? Well, Nick Perham, a senior lecturer at the department of applied psychology at Cardiff Metropolitan University, has done a meta-analysis on the effect that music can have on children’s concentration. His findings show that while some studies in the past may seem to indicate that certain people perform tasks better while listening to classical music, reading comprehension is definitely impaired by music that contains lyrics and/or speech; while he found that listening to instrumental music instead of music which contains lyrics reduces this impairment, his conclusion having looked at all the evidence is that a silent environment is best for concentration and academic performance.

I’ll be honest, I knew all of this and have known it for several years. But perhaps the most striking bit of research I have only heard of recently. This research is about smart phones and the ways in which they can distract us. Now, we all know that these little devices are weapons of mass distraction – I’m not sure even a teeanger would try to pretend otherwise with a straight face. But research carried out in the US came up with some fascinating findings about the extent to which this is the case. Did you know that just the very physical presence of your smart phone – even if face down and switched to silent – impairs your cognitive performance?

The study from America looked at the effect of smart phones on individuals’ cognitive performance. A large number of adults were asked to perform a series of cognitive tests. One group was instructed to leave their phone out in front of them on the desk while they did the tasks, but to place it face down and on silent. Another group was instructed to put their phone away in their bag. A third group was told to leave their phones in another room. And guess what? That’s right. Out of sight is out of mind, leaving your mind free to do the tasks without distraction – those whose phones were nowhere to be seen performed best in the tasks; by contrast, the very physical presence of the phone, even switched off, switched to silent and/or left face down on the desk, was enough to impair the cognitive performance of the candidates whose phones were visible in front of them.

On my regular canal walk the other day I listened to one of the co-authors of this study, Dr. Adrian Ward from the University of Texas, interviewed by Dr. Michael Mosley on his podcast called “Just One Thing”. Ward hypothesised that the smart phone is such a powerful draw – with its lure of games, easy entertainment and social connection – that its very physical presence (even if switched off or on silent) is enough to be an unconscious distraction for the brain. So the physical presence of your phone, even though it is switched off and you have no intention of looking at it, is communicating to your brain that you could be doing something potentially rather more entertaining than what you’re currently meant to be focusing on.

So what can we take from all of this? Well, to me, it’s important that young people understand just what a powerful distraction their smart phone can be, and that they are on board with the idea that they should therefore be putting their devices away (ideally in another room) while they are studying. I am not suggesting that you race into your teeanger’s room right now and wrestle it from them; but if you can persaude them that handing it over for short bursts of time while they are studying is a good idea, then they will thank you in the long-run. Ideally, this conversation should take place and the principle established when children are first allowed access to these devices.