Something which has struck me this year is the huge variation between schools when it comes to handling their mock examinations. Some schools have set them in November, some in December, some in January. Some schools have provided infinite details and guidance as to what the examinations will contain, some have not. Some of my tutees didn’t even know how many examinations they were due to have in each subject and on which topics, although I am hyper-aware that teenagers are not always the most reliable of sources! It is always interesting to ponder just how accurate a reflection of reality I am receiving from the outside …

Mock examinations are important to schools for a number of reasons. As a general rule, they are considered to be an indicator as to whether a student is on target to achieve their predicted grade, although the jury is still very much out on the accuracy of this process. Most schools put their staff through an agony of results analysis, with students being flagged or colour-coded as to whether they are on, above or below target. Sometimes this coding is even passed on to the students. I have heard of schools that hand out the results on colour-coded paper: green for on/above target, amber for close to but below target, red for well below. Apparently it can make for some very interesting reactions, when students who might otherwise have been pleased or distressed at their results were shown them in the context of how they were performing against their targets.

Personally, I don’t like target grades, as I feel that they categorise children unfairly and set up a mindset that is not always helpful. Students with very high targets can feel overwhelmed by the pressure, students with lower ones can feel like the system doesn’t believe in them. So in my eutopia we wouldn’t have them at all. I once met a Headtacher who worked in an outstanding school with outstanding results. They gave every child the same target – to get as far above the pass grade as they could.

One disadvantage of mock examinations is the amount of curriculum time that is eaten up by the very process of examining, a factor which led directly to the demise of the AS/A2 system at Key Stage 5 – losing most of the summer of Year 12 to an examination period was considered simply too costly. In Year 11, however, the mock examination period is mercifully short, with most schools cramming all of their examinations into a two-week or three-week window. The price is paid by the students and by the staff, who face a very intense time during that period.

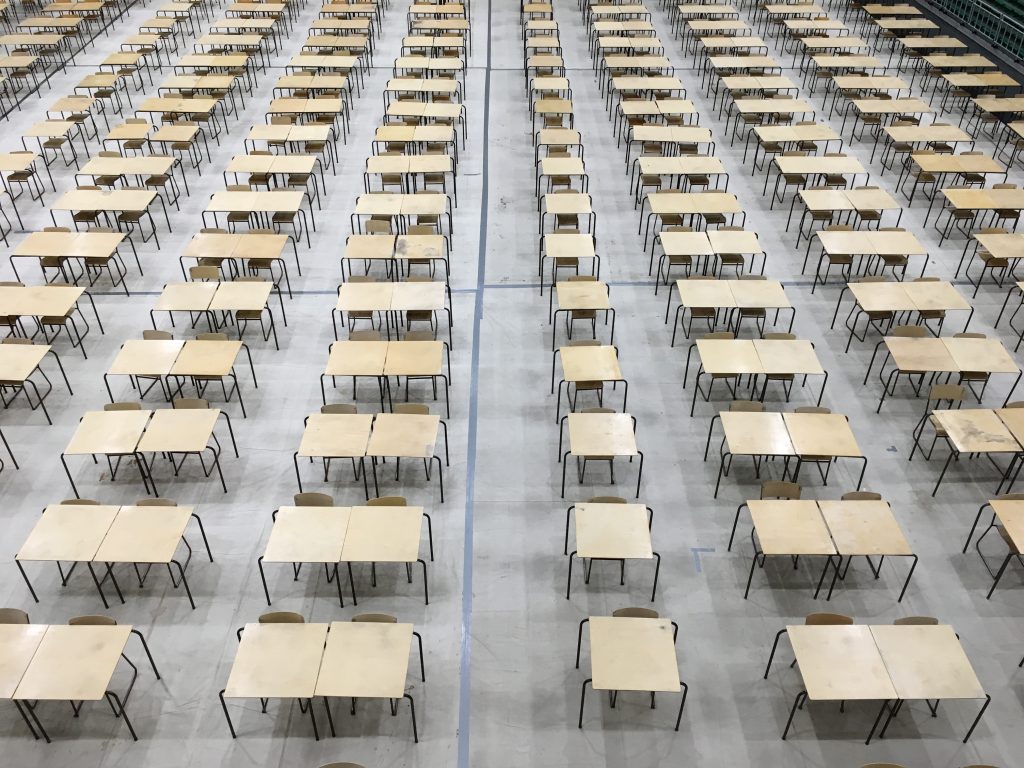

But, despite the gruelling nature of the winter exam-sprint, mock examinations are truly essential for Year 11 students. In many schools this is the one and only time that students experience a practice run of what it will be like to sit their final papers in the summer; many schools don’t have the physical space to facilitate formal examinations for all year groups, so it’s really important for Year 11 to get this one real chance at experiencing what it is like to line up as a year group according to a designated seating plan, file into the room in examination conditions and sit a series of examinations, one after the other. Students experience what it’s like to receive formal instructions from the Examinations Officer, to be told to hand in their mobile phones and check their pockets for banned materials (pretty much everything), to have to have their equipment in an appropriate clear container and to surrender any equipment that is more modern than an analogue timepiece.

All of the above can create tension for students, but it is hugely important for them to experience the process so that they know what to expect in the summer. It can be a real balancing act for schools to create the right atmosphere – just the right amount of gravitas so that students experience the seriousness of the real thing, without sending the entire year group into a state of controlled (or, even worse, uncontrolled) panic.

One of the things which students struggle the most with when it comes to their first experience of examinations is timing, and this is indeed one of the many reasons why mocks are so important. There’s nothing like the full experience of being in a large exam hall and having to work to timed conditions to make you realise that this is something that you need to practise, practise and practise again. There is no point in working on exam-style questions if you are not doing so in timed conditions – in fact, I would argue that doing so could potentially be damaging in the long-run; if a student gets used to tackling a question over a longer period of time, they’re going to struggle to adjust their performance to what is required in the final paper. This is why it’s important to practise things under time pressure from the very beginning.

But mock examinations are more than just an opportunity to experience “the real thing”. They are (or should be) an opportunity to make mistakes and learn from them. Teachers expect some students to read the paper wrong, to answer the wrong section, to tackle too many questions or not enough. The point is that they get to experience the impact of this and learn how important it is to approach each paper in the right way. Beyond that, they also get to dissect their performance in detail and (in an ideal world) receive thorough, individualised feedback from their teacher. The mock examinations should highlight areas of weakness and shine a light on the skills which need honing and improvement.

So what of the worst case scenario? A student totally bombs in the mocks? Well, even that’s not a disaster. I have seen students turn things around in a manner that I might not have believed possible had I not seen it with my own eyes. A real stinker of a performance in an examination can even be the catalyst that some students need to get them focused – if no amount of their teachers or their parents telling them to buck their ideas up has worked, then sometimes totally crashing down to earth with truly disastrous grade can be the ticket.

So do not despair. We have around six months until the final examinations in the summer. That’s more than a quarter of the curriculum time remaining. Time to re-group and time to focus. Success may be closer than you think.