Picture the scene. You’re in a posh restaurant. The sort with linen napkins, thick carpets and snooty waiters. Everyone is dressed smartly and all the subliminal messaging is telling you that – whatever the food is like – you are expected to behave in a certain way.

The couple next to you are hunched over, staring at their smart phones. So are the couple behind them. Your partner is also staring at his phone. When your gaze returns to the table, your own phone awaits. No, this is not an indictment of society’s mass phone addiction, it is an unfortunate situation rendered necessary by the fact that your holiday-provider has decided that Going Digital is A Good Idea. As part of your eye-wateringly expensive holiday package you might be entitled to eat in this restaurant, but apparently you’re not entitled to a menu that you can actually hold in your hands. No, you must access the menu by “following the QR code” using the camera on your phone. Each table has a glass ornament displaying the code, so you whip your smartphone out and away you go.

It was not just the fact that seeing people scrolling on their phones in a restaurant was depressing – which it was. It was also the fact that accessing the menu in this way afforded no tangible gains whatsoever: it was, in fact, a substantially sub-optimal way of looking at a menu. The very need for scrolling was an irritation, when real menus are arranged in a way that allows you to scan the whole offering in one. A traditional menu would have been- quite simply – a hundred times better. Even my husband heartily agreed, a man who had a career in software engineering and is a natural lover of all things digital.

This spectacularly pointless switch to digital puzzled me for the rest of the holiday. With the best will in the world, why would somebody do this? Have we actually hit the point where some people believe that things are made definitively better purely for the reason that they are sprinkled with digital fairy dust? The quite extraordinary stupidity of the whole thing was rendered even more ludicrous by the fact that the holiday company did not even have the imagination to exploit the (albeit slim) advantages that “going digital” could bring to the party. For example, if they were so determined to go the digital route, then why not share the QR code with customers ahead of time and encourage them to start choosing their menu options in advance? This would at least have added a whiff of anticipation, although I still would argue that a traditional menu would have been infinitely preferable once we were sat in the restaurant itself. Easy advance-sharing was literally the only potential advantage I could imagine arising from the digital model, and they didn’t even bother to do that. So, the gormless march towards everything going digital advances, it seems, with no thought applied either to the potential consequences or to how to actually reap the potential advantages it might afford.

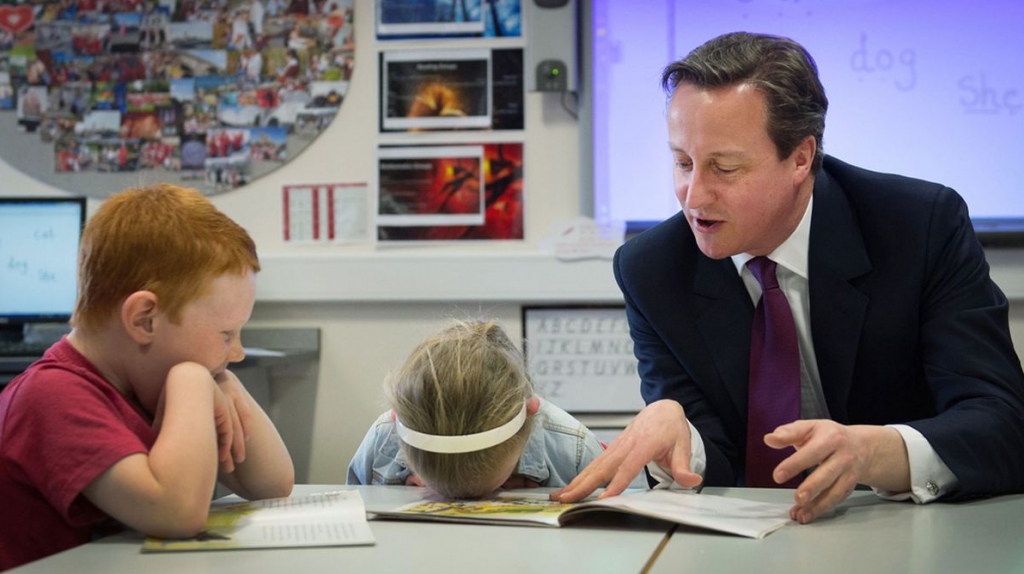

Increasingly, secondary school students are provided with “everything they need” online. While digital tools will have meant some investment on the school’s part, I am suspicious that a lot of what happens now is actually about reducing their photocopying budget, an undeniable thorn in the side of every HoD who has responsibility for their department’s costs. Honestly, what schools spend on technology generally pales into insignificance when compared to their yearly photocopying budget. While really successful schools who are getting fantastic results and impressive Progress 8 scores have broadly shifted towards the use of printed booklets for the students and moved away from digital presentations on the part of the teacher, vast swathes of schools (including in the private sector) have shifted towards a digital model, where everything is presented to the students electronically and nothing is printed out. Ker-ching.

I have worked with dozens of students in this position and have seen the disastrous fallout of what this digital model does for students’ learning and understanding. Inevitably, like anything inherently flawed, it is the already-disadvantaged that it leaves behind. People seem to assume that being “disadvantaged” means a lack of access to expensive technology and it is true that there can be glaring differences between what an affluent child has access to by comparison with one who is eligible for free school meals. But this is not the only way that students can be disadvantaged and it is vastly outweighed by other, more serious handicaps. Think prior attainment, think organisational skills, think access to an ever-increasing range of vocabulary, think time and space. Students who are already struggling in class for a myriad of reasons – some of which may or may not relate to poverty – are demonstrably left behind when adults demand that they manage both their time and their resources in such an abstract way, often without guidance.

There is so much nonsense talked about the younger generation being fully au fait with the full range of digital technology on offer, as if being born in the digital age bestows young people with an innate knowledge and understanding of the skills and mindset required to navigate towards progress in the modern age. The reality is that most kids are completely clueless when it comes to managing their learning remotely. Of course they are! Just because a child has been pressing icons on the screen of an iPad since they were a toddler, this does not imbue them with the organisational skills required to manage their learning online. To assume so would be like assuming that a toddler who has mastered the fun that can be had from a pop-up reading book is thus fortified with the skills and knowledge required to negotiate a library full of journals, encyclopaedias and reference manuals.

An increasing number of students that I work with are studying the WJEC/Eduqas GCSE syllabus, the creators of which produce a simply baffling array of resources that even I took a while to get my head around. Some of them are aimed at teachers, some of them in theory designed to be student-friendly. Most schools dump all of these resources into an area where students can access them, a collection of ponderous PDF files that are long and academically challenging. The one file which is explicitly aimed at students is designed as a student booklet, with space in which students can write their translation and notes. Most schools don’t even bother print this one out, instructing the students to work electronically. I have tutees who have not held a pen in class for years, so wedded is their school to the use of tablets or Chromebooks. I could honestly weep for their basic skills and feel outraged that so many schools are so blatantly ignoring the research that we have on the link between the use of a pen and memory. These students come to me with simply no idea what they have supposedly studied, what materials are in their possession and what they are supposed to do with them. They are completely overwhelmed and can’t even articulate the basic content that they have theoretically covered in class.

Technology is an absolute wonder. In the last few years, I have embraced online learning to the extent that I have made a career out of it, I have embraced the time-saving advantages of AI and I am always open to the advantages that technical advances can bring. As someone in possession of the world’s worst sense of direction, I find the smartphone genuinely liberating and life-changing, as it enables me to negotiate my way confidently. It even knows all the local pathways! As someone with poor eyesight, I love the fact that there has been an explosion in the availability of audiobooks, and that I can now access most books and articles in a format that allows me to manipulate the size and shape of the font as well as the colour of the background. This is all wonderful! Believe me, I love technology! But I am heartily sick of two things that the digital snake-oil salesmen seem to have successfully convinced society of: firstly, the blind assumption that digital is always better, when in fact people should be asking themselves whether it is better and if so why – what other advantages might the technology bring and what are the potential pitfalls? Secondly, I am tired of the assumption that children born in the current epoch are all miraculously imbued with innate digital skills and knowledge, a bizarre fantasy which seems thoroughly ingrained, despite the ever-increasing pile of evidence to the contrary.