Book 2: radical changes

Last week I reviewed the 5th edition of the Cambridge Latin Course Book 1. While the changes were notable, they were perhaps only apparent to someone who knows the course inside out. By contrast, the moment one opens the second book and compares it to its 4th edition predecessor, it is apparent that the changes here are far more radical. From the very first set of cartoons, the difference it striking.

Okay. Full disclosure from the outset: I don’t like Book 2. As a result, I’m afraid that this review is not going to be gushing. It is difficult enough to hold the attention of Year 9 (especially once they’ve chosen their options, which happens remarkably early in the academic year); with CLC Book 2, it was nigh on impossible and I have never felt so liberated as when I ditched it altogether. Yet the authors of the 5th edition have clearly made significant improvements to make the transition from the first to the second book is more palatable. To date, students have struggled to move on from the loss of Caecilius and other favourite characters, so the authors of the new edition have done the right thing in attempting to give Quintus more character in Book 1 and providing him with a new companion to accompany him on his travels. I retain my reservations about Book 2, even in its new format but, with such radical changes employed, it is undeniable that the authors have given it their best shot to adapt it.

The first stage of the book (Stage 13 in the series) has been radically altered. The lazy slave motifs of yesteryear are gone, and the opening cartoons demonstrate this from the outset. The monumentally dull opening story Tres Servi has been removed and replaced with a much better story entitled Romanus Vulneratus, which introduces us to Salvius in the distance, observed by a local farmer and his family. This is a much cleverer way to spark interest in the story Coniuratio which follows, and which we now hear as an explanation as to how the wealthy Roman Salvius came by his wound. I think the very idea of seeing these Roman characters through local eyes is excellent and a terrific approach taken by the authors throughout the new edition.

Rufilla is given a more dominant role, notable in the way the cartoons are presented and how the story of Bregans is shaped around her rather than Varica. The story is now divided into two parts, but still introduces the dog sent as a gift by King Togidubnus (renamed in line with updated research). A new character of Vitellianus is introduced and there is much better story-telling, with Rufilla noticing that her husband is wounded, and much less “Romanising”, with Bregans no longer being the stupid, lazy slave. The twins, Loquax and Anti-Loquax, are notable by their absence in this Stage. Salvius Fundum Inspicit has been renamed Fundus Britannicus, and once again this story has been adapted to reflect the viewpoint of local farmers living under the Roman occupation.

The order in which the grammar is introduced throughout Book 2 remains the same. For example, Stage 13 still introduces the verbs volo, nolo and possum used with the infinitive, and this grammatical point is rather better represented throughout the stories than it was before. I still ache for the lack of exercises provided; regretfully (and – as I undetstand it – deliberately) the CLC still relies heavily on the classroom teacher supplementing students’ studies. The authors have moved the practising the language exercises to the back of the book and added in extra comprehensions in every stage; given that the exercises require extensive vocabulary support, I do wonder whether the authors have considered just how much work the CLC demands of the clasroom teachers who work with it. When I think of the thousands of Latin teachers all over the country typing out hundreds of exercises on the most basic of grammatical principles, it makes me want to weep at the inefficiency. Changes have been made to the vocabulary checklists, largely (although not entirely) to better represent the list of words required at GCSE. I retain serious concerns about the vocabulary used outside of the checklists, which I shall come back to later.

The authors have decided to ditch the motif of Rufilla as the nagging, 1970s-style housewife, which is a great relief. She has an equally if not more dominant role in Stage 14 as before, but the row between her and Salvius, in which she was portrayed as fickle and spoilt, has been replaced with Familia Occupata, in which her focus is preparing the guest bedroom – a much better way to build anticipation about who that guest might be. The household slaves are also much better represented throughout Stage 14 in the build up to Quintus Advenit, now renamed Familiaris Advenit to allow students to discover the guest’s identity for themselves as they translate. The story of the silver tripods remains, followed by a new story for comprehension, which once again replaces the exercises now moved to the back of the book. This certainly cements the “reading course” approach – to those of us unconvinced by that philosophy, I fear it is another nail in the coffin for the CLC. Many teachers, however, will be very pleased to see some beginners’ level literary criticism brought in – I am aware that some schools take this approach with the CLC already and it seems the team has taken it on board.

It is notable that the background sections, which continue to exploit the idea of the characters appearing as talking heads, are now spread out more widely throughout some of the stages, meaning that teachers are perhaps more likely to weave the background material into their lessons as originally intended by the philosophy of the CLC. Women are better represented (i.e. they are represented full stop) and there is a pleasing exploration as to why we know so little about them and indeed about anyone who was not rich, male and powerful. I will not explore and discuss the changes to the background in depth because – like many state-school teachers, I had no time for them anyway and therefore lack the expertise. Suffice to say it is clear that the changes are radical, thorough and for the better, so schools with the time to explore them in depth will have much better quality material to work with.

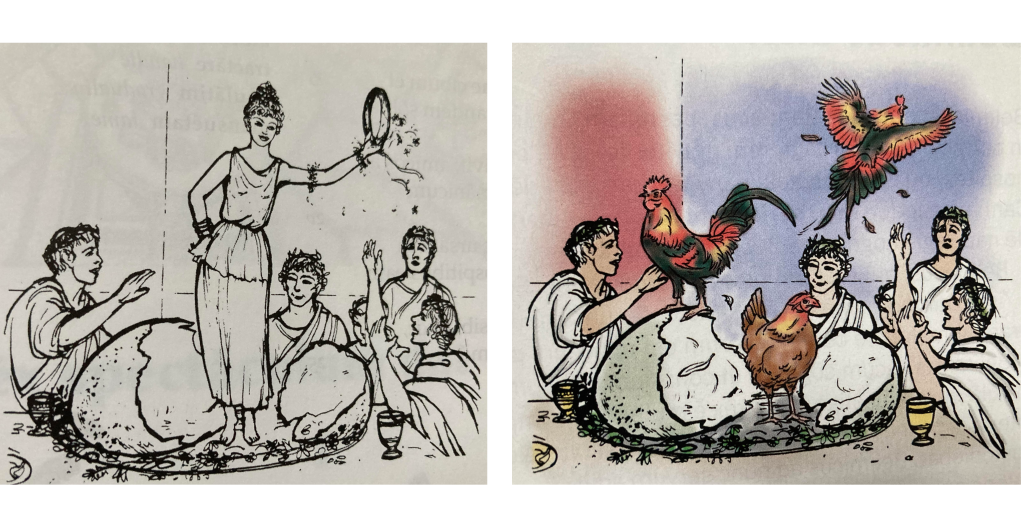

The changes to the stories in Stage 15 appear less radical and therefore what’s most noticeable is once again the practising the language being a comprehension rather than exercises, which have again been moved to the back of the book. There is a welcome change to the cartoons at the start of Stage 16, which previously had the most extraordinary representation of enslaved people with dwarfism, randomly juggling for the entertainment of some dinner guests. While it is absolutely undeniable that the Romans did this kind of thing, to make this image the only representation of disability within the pages of the CLC and drop it in without comment was frankly appalling and something that I am very glad to see the back of. These unfortunate (and nameless) characters have been replaced with the previously absent twins, named in previous editions as Loquax and Anti-Loquax, who make an appearance here although are not named. In the same set of cartoons the authors have also removed the bizarre and frankly distracting moment when a dancing girl appears out of an enormous egg and have replaced her with some birds. Below is the image as it appears in the 4th edition followed by its replacement in the 5th.

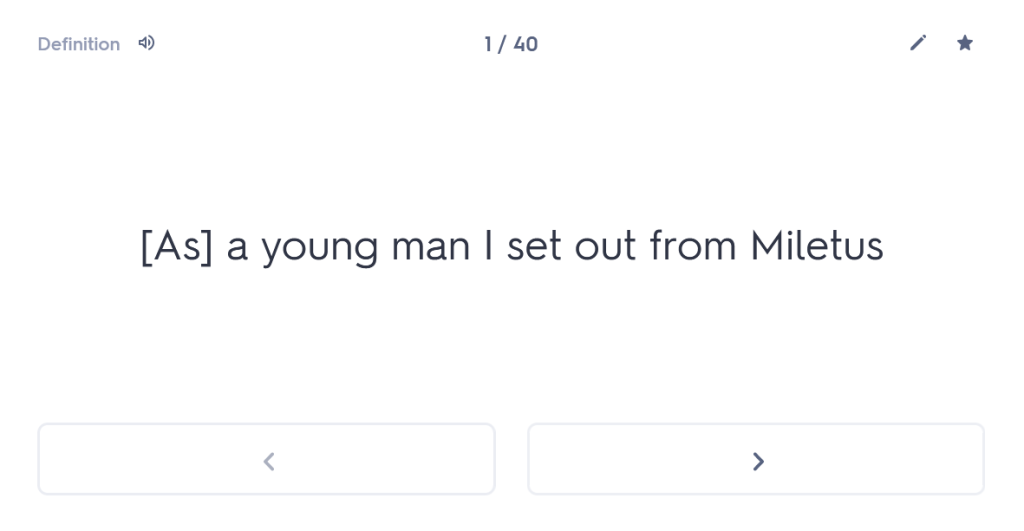

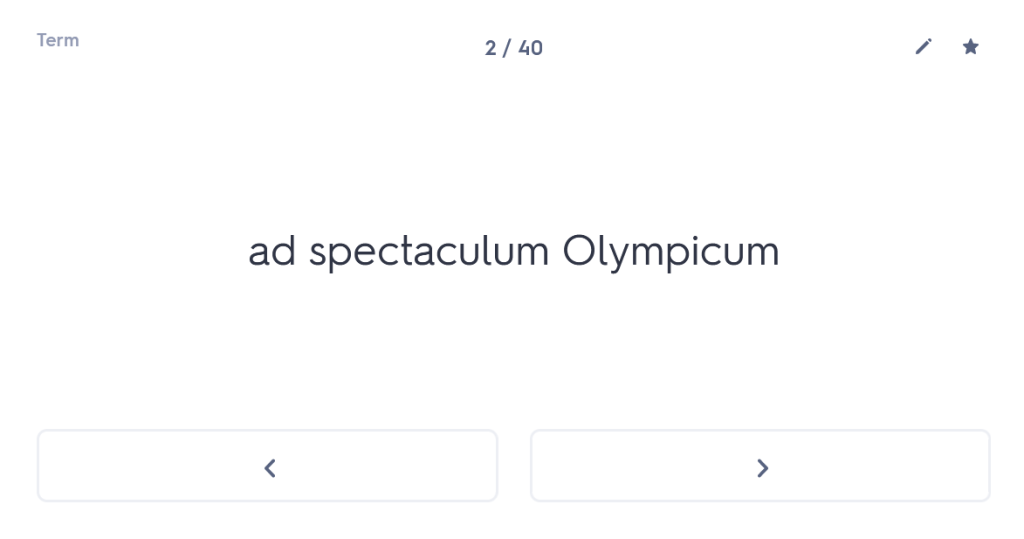

I was pleased to see Quintus De Se still in place, as this is a pivotal and grammatically useful story, where Quintus articulates his trauma and which I used to use in an adapted form to test students on verb endings. The story has some pleasing tweaks, incorporating the fate of Lucia, Quintus’s sister, and explaining how Clemens found the two siblings after some time and gave Quintus the ring handed to him by Caecilius at the end of Stage 12 (which to my recollection was never mentioned again in previous editions).

But Stages 15 and 16 in general are the point where the CLC starts to go a bit wild, in my opinion. To my dismay, the authors have chosen to keep the storyline about Belimicus, the tedious boat race and the bear – in my experience, children honestly do not find these stories even half as exciting as the authors seem to think they are, but maybe other teachers have found differently. And yes, of course, I used to throw myself into it, get the children to act out the stories, draw diagrams of the race, label what happened at each point, you name it, I did it. We were all doing it back in 2010. Some teachers are still doing it. What an epic waste of class time! Let’s focus on the language: in my experience, by this point in the course, the amount of unusual vocabulary weighs so heavily upon students that they find themselves endlessly frustrated by the translation process and therefore lose heart with it. My concerns in this regard are perpetuated in this new edition, where the authors have elected to continue to use relatively unusual vocabulary to introduce and demonstrate core grammar. As just one example, the sentence which demonstrates the pluperfect in Stage 16 is constructed almost entirely out of words which do not appear on either of the GCSE specifications, nor in Dickinson’s One Thousand: artifices, qui picturas pinxerant, peritissimi erant. Other than the verb to be and the relative pronoun, these words are frankly irrelevant and I think it’s madness, given the depth of the overhaul that this course has undergone, that the authors haven’t taken the opportunity to resolve this issue. I suspect it is because they genuinely don’t see the excessive amount of unusual vocabulary as an issue to the extent that I have found it to be in the classroom.

Stages 17-20 remain, as in prior editions, a flashback to Quintus’s time in Alexandria, with the notable change that his sister Lucia, introduced in the new 5th edition of Book 1, is also a survivor and therefore joins Quintus on his travels. An extra story in Stage 17 entitled Tres Aves focuses on her and makes further pleasing mention of the siblings’ losses in Pompeii – in previous editions, there wasn’t enough opportunity taken to make links for the characters with their past, so this is really good to see – the course and its narrative certainly feels more coherent now. Stage 18 retains its focus on Clemens, his Alexandrian shop and the protection racketeering and Stage 19 still introduces the characters of Aristo, Galatea and Helena – mention is now made in the cartoons that they are friends of Barbillus, which goes some considerable way towards maintaining the thread of the storyline better than in previous editions. Lucia is also woven into the stories of Stage 19, with this being the focus in a total re-write of Dies Festus. The story of the hen-pecked Aristo has – mercifully – been removed and we are then into endgame, with the story Venatio depicting the scenario which will finish off Barbillus, who has thus been much better woven into the extended narrative throughout Book 1 and Book 2. Barbillus’s demise seems much more poignant, not just because he has been better painted as a character and friend of the family, but because his will is represented nicely in the book and the relationship between him and the siblings Quintus and Lucia is much more explicitly drawn.

While the storyline hangs together really well and the narrative is undeniably entertaining, I maintain that the vocabulary of Book 2 is overwhelming for students and that this burden will continue to cause them to lose interest, both in the narrative and in the language itself. Were I still a classroom teacher I do not believe that I would have re-embraced the use of Book 2, solely due to this fact. While Book 1 requires heavy supplementation, this is just about manageable and definitely worth doing. But when I found myself glossing virtually every single word in a lengthy story – as I did for Book 2 – and when those words are, on the whole, not useful for GCSE, I had to ask myself what purpose the book was serving. My professional judgement that Book 2 was not serving my needs as a time-pressed classroom teacher sadly remains the same having examined the 5th edition: the authors simply haven’t addressed the core reasons behind why I ditched it in the first place. Others will feel very differently of course, and I suspect that ardent fans of the course will be delighted with the changes.

I was always going to be a tough audience, with my fundamental dislike for Book 2 and my sincere belief that it is pretty much irreconcilable with the needs of the classroom teacher, particularly in a comprehensive setting. I remain convinced that the CLC and its usefulness starts to crumble beyond repair at this point. The passages are packed with too much difficult, irrelevant and overwhelming vocabulary and – perhaps most crucially of all – far too much relies on the classroom teacher to produce countless supplementary worksheets; the requirement to do this is so onerous that one is left wondering why one would invest in these expensive text books at all, when they fail so fundamentally to provide the core content of a Latin course.