A conversation with one of my younger tutees this week reminded me just how toxic classroom disruption can be. While rueing his poor performance in a recent test, the boy expressed real frustration about the situation in his Latin class. “Some kids just see it as their job to mess around” he said. He even reported that the situation had brought his teacher to tears in the past.

At even its most minor level, any form of classroom disruption is an issue for all learners. Children who may be struggling with the material go unsupported because their teacher’s attention is taken by the disruptors in the class (who may, of course, be struggling themselves). Schools which have not yet faced up to the inescapable fact that impeccable behaviour is the central, non-negotiable foundation on which all teaching and learning is built, those schools will continue to let young learners down.

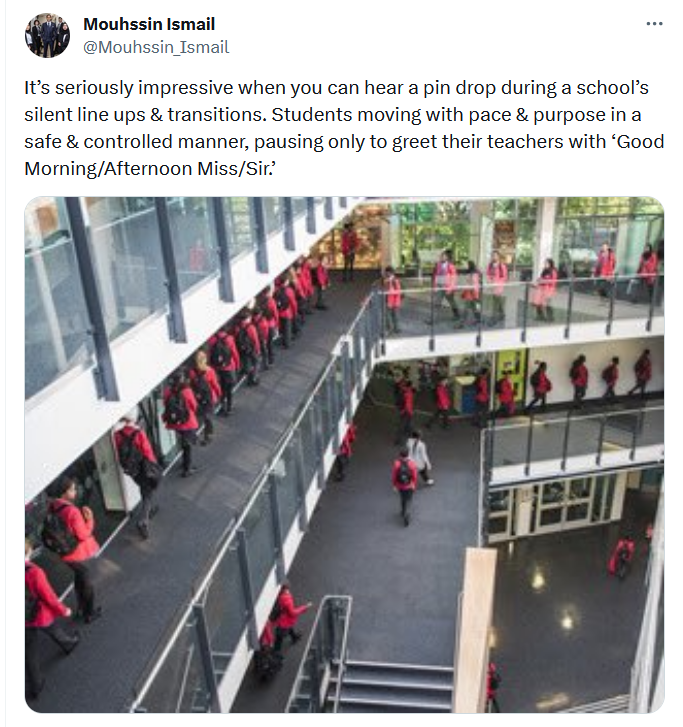

One of the things I find most puzzling about the teaching profession is that we cannot seem to agree on how to manage behaviour. Debates continue to rage about schools which set the bar high, with cries from numerous educators claiming that vulnerable students and/or SEND students cannot handle such a high bar and that clear boundaries such as the use of SLANT in classrooms and the insistence on silent corridors are oppressive and stifling. I find this baffling, not to mention an insult to the children with those needs. As someone who has worked in schools rated Good or Outstanding for behaviour, I can tell you that there were times when I was frightened in the corridors. There were times when I felt pushed around and intimidated by some students. There were times when I felt humiliated. What this all translates to in schools with behaviour that ends up being classified below Good I cannot even begin to imagine. Moreover, if I as a middle-aged adult felt like this in the school corridor, how did our most vulnerable students feel?

A recent survey on Teacher Tapp, a daily survey app for classroom teachers, highlighted the ever-increasing use of ear defenders by some students in our schools. As I pointed out in response to the discussion, I find their necessity deeply depressing. How did we get to the point where we simply accept that some school environments are too noisy and overwhelming for some of our students? Like that’s ok? And like noisy, boisterous environments aren’t actually a negative for all learners? How on earth did we end up in a situation in which the kind of equipment required by men on building sites using machines to break up concrete becomes a necessity to protect our students from the environment in our schools?

Let me tell you about my one of my own experiences in the classroom. I was sent to an expensive girls’ boarding school (although I didn’t board, I was one of a small percentage of day pupils). In Year 9 (or the Upper Fourth, as it was called would you believe) I was part of a Classical Civilisation class run by a young female teacher whom I shall call Miss Jones. Poor Miss Jones was a sweet, kind and well-meaning woman, who no doubt went into teaching because she cared about her subject and wanted to share it with the world. I suspect she had no training, because in a private school in the 1980s teacher training was considered very much optional and barely even desirable. The school was tiny, consisting of 400 girls in total and had a pretty strict regime – for example, silent corridors. The Head was terrifying – genuinely so. But poor Miss Jones, with her reticent nature, her lack of training and her lack of experience, had no control over our class. One girl was particularly disruptive. I shall call her Millie. Millie was taller and looked older than most of us. She terrified many of us and was a merciless bully to some. That included Miss Jones. Millie refused to cooperate with the class, to the extent that she would not sit where she was told, she would not participate in the class in any way, she would not even unpack her bag. She would lay her head on the desk in a flagrant show of disdain. Miss Jones’s methodology was to ignore her and try to teach around her, but behaviour in general was so poor that we all learnt very little. She never received any support or help with the situation and did not last long in the job.

I share this to illustrate the fact that issues with poor behaviour occur in all schools. Another recent survey from Teacher Tapp, carried out just this week, indicates that student behaviour, alongside workload, is now the overwhelming reason why teachers are leaving the profession in their thousands. There is much talk about “challenging” schools and understandably so, because getting behaviour right in such places has very real safeguarding issues, as explained in this brilliant blog post which I have cited many times before. Yet I would like to highlight the fact that behaviour that is disruptive enough to impact on teaching and learning goes on everywhere – in schools rated Good or Outstanding, in grammar schools and in private schools. Some of what I hear from my tutees would not be out of place in a chapter of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies – and these are the sorts of schools with Latin on their timetable.

While I do not wish to promote panic or cause any pearl-clutching, I do believe that disruptive behaviour in our schools is an issue that nobody wants to face up to. Nobody – whether they are a parent or a teacher – wants to believe that our children’s education is being hampered by disruption in the classroom. It is hard for all of us to accept. While writing this blog post, a memory from close to a decade ago came back to me with a jolt. It is a comment made by a boy in one of my past Forms, a boy who was one of the most disruptive members of the class (and indeed the school). “Your PSHE lessons are like watching a YouTube video with crap internet, Miss: you keep buffering.” I recall being somewhat non-plussed by this rude remark, one which was called out across the class and interrupted the flow of the lesson in exactly the way he was describing. Out of the mouths of our not-so-innocent babes can come the real truth: my ability to share information was being constantly put on pause, meaning that the flow of explanation was consistently and endlessly interrupted. This was painfully obvious, even to the members of the class who were causing most of the interruptions, a fact we should perhaps give some thought. I remember being further stunned when an out-of-control student expressed his desire to join the army; as I picked my jaw up off the floor and used it to point out to him that he would have to behave in the army, he said “yeah. That’s the point.” I’ve never forgotten the fact that he knew he needed more discipline than we were providing for him. We let him down. Badly.

So, back to my tutee, who was complaining about the behaviour in his Latin class. He described exactly the kind of intermittment “buffering” that the lovely Liam pointed out to me a decade ago, so it sounded all-too familiar, but this week it really hit me just how truly appalling the situation is for so many young learners and just how many of them have come to accept it as part of their school experience. “Just as I think I’m starting to get something,” he said, “the teacher has to stop and then I’ve lost it all over again.” That’s when my heart broke a little.

It’s hard to know who needs to hear this but I suspect it’s all of us: classroom teachers, parents and senior leaders all need to face up to the problem for what it is and reassert our right and our responsibility to be the adults in the room. Disruption – low-level or otherwise – is kryptonite to every child’s understanding and progress. To ignore this is to let all of our children down.