Classroom teachers are expected to be psychics. According to the Teachers’ Standards, which are many and complex, every classroom teacher must not only understand how children think and learn but must know when and how to differentiate appropriately, using approaches which enable pupils to be taught effectively; they must have a secure understanding of how a range of factors can inhibit pupils’ ability to learn and how best to overcome these; they must have a clear understanding of the needs of all pupils, including those with special educational needs, those of high ability, those with English as an additional language and those with disabilities; they must be able to use and evaluate distinctive teaching approaches to engage and support all of these different young people … and all of this must happen while there are 30 of these diverse learners in the same room.

Much of what is demanded of the average classroom teacher is impossible. I say this not to be a doom-monger or to preach the acceptance of mediocrity – far from it. Throughout my career I strived to be the best teacher I could possibly be. Yet in reality, we cannot be all things to all men and we cannot possibly fathom the inner workings of every single one of the minds that are sat in front of us.

I have written numerous times on the differences between classroom teaching and tutoring but this week something hit me that had not occurred to me before. While I have always been aware that one-to-one sessions give me an insight into the misconceptions each child may have and thus the ability to address those, it has not previously dawned on me that tutoring a large number of students in the way that I do has given me a broader insight into how children think and learn in a way that I could not have experienced as a classroom teacher. Working one-to-one means that I get to listen to how my students think and reason in real time.

It is often said by modern cognitive scientists that education has placed too much focus on the diversity of learners in the past. While every parent likes to think that their child has a unique set of needs that can only be met in a unique way, the reality is that there is far more that unites young learners than divides them. We now know a great deal about how memory works and how best to support students with the learning process: this is not to say that some will not find it harder than others and require more time and effort than others, but broadly speaking the approaches that work for those with special educational needs in fact work well for the mainstream classroom as a whole. If you tailor your classroom towards providing the best learning support for your neediest learners, everyone benefits as a whole.

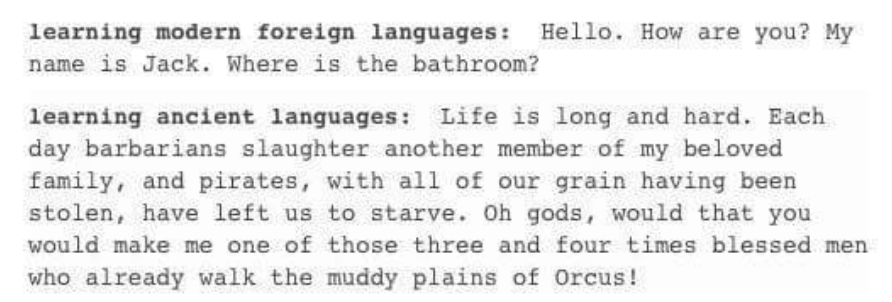

Working one-to-one with the huge number of students that I do has furnished me with a real insight into how students tackle the process of translating and what the common pitfalls are when they are doing so. It has also provided some perhaps surprising insights into which constructions that children tend to be able to translate on instinct, without a full grasp of understanding. This information is actually gold dust and links to what I blogged about last week – the necessity of designing a curriculum around the learners sat in front of you and in relation to the time you have available as well as the end goal when it comes to examinations. I have realised in the last year or two that there are some complex constructions which many classroom teachers tend to focus too much time on, to the detriment of the basics, when in fact many students could translate those constructions without difficulty so long as they had a grasp of their verb and noun forms and their vocabulary.

Working one-to-one has given me more of an insight into what doesn’t need to be taught as well as what does. While most of my students have gaping holes in their basic knowledge, many of them have spent an unnecessary amount of time being taught things that they do not need to understand in detail. Sometimes, a construction has been so over-taught that a child has been left in complete confusion; their natural grasp of it, one which they would in all likelihood have stumbled upon if given the right basic tools and a decent dose of confidence, has been lost forever.

I am still pondering what to do with these insights as it occurs to me that they could quite honestly be of enormous use to any classroom teacher who is willing to listen. For now, my understanding of how children go about acquiring the skills that they need to do well in Latin is ever-increasing and remains endlessly fascinating to me.